02

03

Tax on Investment Income

- Savvy Tax Move #2: Avoid Short-Term Capital Gains

- Savvy Tax Move #3: Match Gains With Losses

- Special Section: What Do You Do With a Large, Concentrated Stock Position?

04

Deductions and Credits

- Savvy Tax Move #4: Bunch Cash Gifts

- Savvy Tax Move #5: Give Appreciated Securities

- Savvy Tax Move #6: Combinations

- Special Section: Sunsetting of Tax Cuts and Jobs Act Benefits

05

Legacy Planning

- Savvy Tax Move #7: Choose Account Type

- Savvy Tax Move #8: Shield Wealth

- Special Section: Legacy Planning Can Help You With Charitable Giving

- Savvy Tax Move #9: Two-For-One

Is this conversation (or a variation of it) familiar?

Jimmy walks into his accountant’s office and says, “I have to pay for my daughter’s college but I really don’t want to sell my stocks and pay tax on the large gains. How can I get around paying the capital gains tax?”

Sally, his accountant, ponders his question for a bit, and responds with, “Well, there are a few options for avoiding tax on your stock winners—gifting, planning, and dying.”

Jimmy leans in and says, “Tell me more.”

Sally describes the tax benefits of gifting appreciated stocks to charity. She then proceeds to explain how planning ahead can help folks like Jimmy pay taxes in the years that are most advantageous to him.

Not one to give up easily, Jimmy asks, “And the dying option?”

Without pause, Sally quips, “When you die your heirs get an automatic step up in their cost basis—meaning the stock’s cost basis resets to the current market price so there isn’t a gain from a tax perspective…it’s the classic tax-avoidance maneuver!”

Now that puts an interesting twist on Ben Franklin’s famous saying,

in this world nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes”… Ben Franklin

Ben Franklin

…and it’s also probably not the answer Jimmy sought!

But it brings forth a very common problem for many investors: How can you minimize the tax hit on your investment portfolio? And taking it a step further for retirees or those nearing retirement, how can you reduce taxes in retirement from all sources of income?

Alas, we’re here to help. Our financial planning team confronts these quandaries every day to help retirees structure their wealth in a tax-efficient manner. Because if you don’t plan for the erosion from taxes, you can lose nearly 40% of your money in some cases, especially after considering the impact of state-level taxes.

In this report, we answer three popular questions for you:

- What taxes do I have to pay, and at what rate?

- Which type of account maximizes after-tax income and growth?

- What strategies should I consider now—and later—to reduce taxes for myself and my heirs?

To print this report or save it as a PDF, click here.

Before we begin, we want to note that while we can offer insights on tax efficiency and discuss tax considerations in a general way, Motley Fool Wealth Management does not (and is not permitted to) provide tax or legal advice. Remember, the discussion of tax strategies in this report is intended for educational purposes only and should not be relied upon as personalized tax or financial planning advice.

If you need such advice, please consult with your own tax and legal professionals before making any decisions.

With all that said, let’s dig in!

Taxes, Taxes, Taxes

Taxes, Taxes, Taxes

The hardest thing in the world to understand is the income tax. Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein

Let’s start with answers to two straightforward questions:1

What is a tax?

A tax is a mandatory payment or charge collected by your local, state, and federal government from individuals—like you—and businesses.

Why do we pay a tax?

To help cover the costs of general government services, goods, and activities.

Most people pay both federal and state and local taxes. On the federal level, taxpayers primarily are concerned with two types of tax—ordinary income tax and capital gains tax. There are different rate breakdowns for these based on income level, but in general, long-term capital gains tax is at a lower rate than ordinary income tax (which is also the same rate for short-term capital gains). At the state level, income tax can also be a major expense.

Comparison of Long- and Short-term Capital Gains Tax

Long-Term Capital Gains

| Tax Status | Single | Married Filing Jointly |

|---|---|---|

| 0% Tax Rate | Up to $48,350 | Up to $96,700 |

| 15% | $48,351 – $533,400 | $96,701 – $600,050 |

| 20% | More than $533,401 | More than $600,051 |

Short-Term Capital Gains

| Tax Status | Single | Married Filing Jointly |

|---|---|---|

| 10% | $0 – $11,925 | $0 – $23,850 |

| 12% | $11,926 – $48,475 | $23,851 – $96,950 |

| 22% | $48,476 – $103,350 | $96,951 – $206,700 |

| 24% | $103,351 – $197,300 | $206,701 – $394,600 |

| 32% | $197,301 – $250,525 | $394,601 – $501,050 |

| 35% | $250,526 – $626,350 | $501,051 – $751,600 |

| 37% | $626,351 or more | $751,600 or more |

Source: Tax Foundation. Rates are for federal taxes for the 2025 tax year. Accessed May 27, 2025.

As we mentioned, the applicable rate for these taxes depends on your level of income. But as a retiree, you might think your income is nearly nonexistent, because you’re no longer working and don’t receive a paycheck. However, from a tax perspective, that’s probably not true. The federal government imposes tax on “income from whatever source derived,” which not only includes your wages earned, but also income from rental properties and other income-generating assets.2 In addition, it taxes Social Security benefits and distributions from pensions and other retirement accounts as income.

Yup, you heard that right—the government taxes much of the money you rely on in retirement. We can debate the fairness of this or your disdain for taxes, but suffice it to say, it SEEMS like there’s almost no way around paying a hefty retirement tax bill. Or is there?

A tax loophole is something that benefits the other guy. If it benefits you, it is tax reform. Russell B. Long

Russell B. Long

Tax-Efficient Wealth Planning

We think individuals have some options when it comes to how much and when they pay their taxes. In other words, while we cannot always eliminate taxes completely, there are several legal ways to structure income to mitigate your tax bill. When considering tax-mitigation strategies, we look at two sides of the tax equation—income and deductions. We’re guided by two broad principles:

While everyone’s situation is different and these are highly personalized planning decisions, we adhere to six rules of thumb to shrink your general tax burden.

Rule 1

Pay tax in stages of life when your income is relatively low, and therefore your tax rate is also low, and defer tax in stages of your life when your income is relatively high.

Rule 2

Understand the value of the standard deduction. From a tax perspective, accumulating deductions like medical expenses, mortgage interest, and charitable giving is only helpful if you are already over the standard deduction threshold.

Rule 3

Consider the timing and manner of charitable contributions to optimize your tax deduction AND your impact.

Rule 4

Gift cash as a last resort.

Rule 5

Consider a Roth conversion if you want to give to your heirs, but not to charity. (Charities are tax-exempt so you should gift pre-tax money!)

Rule 6

Be aware of how your different income streams have unique tax efficiences. For example, self-employment and real estate earnings are taxed as ordinary income, which allows you the opportunity to deduct expenses against it prior to taxation.

Applying these general tenets to the accumulation phase

We believe if you're early in your career when your income—and tax rate—is usually comparatively low, you should save in this order:

- First, contribute up to the match amount in an employer-sponsored retirement plan to receive the “free” money from your employer.

- Then, add the maximum to a Roth IRA, not a traditional IRA. Why a Roth? Because while the money put into a Roth is after-tax, at this stage, you’ll likely have a lower tax rate than later in your career. All withdrawals from a Roth are tax-free and don’t count toward income.

This is beneficial in retirement for several reasons, which we will discuss later, but two major advantages are that withdrawals 1) don’t count as income, so it keeps your tax rate low, and 2) won’t raise your Medicare premiums.

And if you’re in the middle or end of your career—near your peak earning potential— defer income and push taxes to the future. At this stage, max out your pre-tax contributions to your employer-sponsored retirement plan. Also, think about tax deductions. For example, if you want to give to a charity, consider bunching your gifts instead of giving in a steady stream to maximize your deductions.

Our tax code is so long it makes War and Peace seem breezy. Steven LaTourette

Steven LaTourette

How can you lower your taxable income? Think tax breaks!

How do you get tax breaks? Generally through credits and deductions. Here’s how the IRS defines each:3

Credits can reduce the amount of tax you owe or increase your tax refund (and even give you a refund if you don’t owe any tax!).

Deductions can reduce the amount of your income before you calculate the tax you owe.

Individuals can receive credits for five categories:

- family and dependents

- income and savings

- homeowner

- electric vehicle

- health care

Likewise, there are five buckets of deductions:

- work-related

- itemized

- education

- health care

- investment-related

Of course, there are income limits and other criteria for taxpayers to take advantage of these breaks.

Holding on to more of your money in the spend-down phase

At the point in your life when you can take advantage of the fruits of your labor—like retirement—you’re probably in the spend-down phase. This stage can look different for everyone. For instance, you may want to create a budget so that you use every last penny before you pass away. Or you may want to touch only interest and keep the principal in your coffers for charity and your heirs into perpetuity. Most people tend to fall somewhere in the middle of this spectrum.

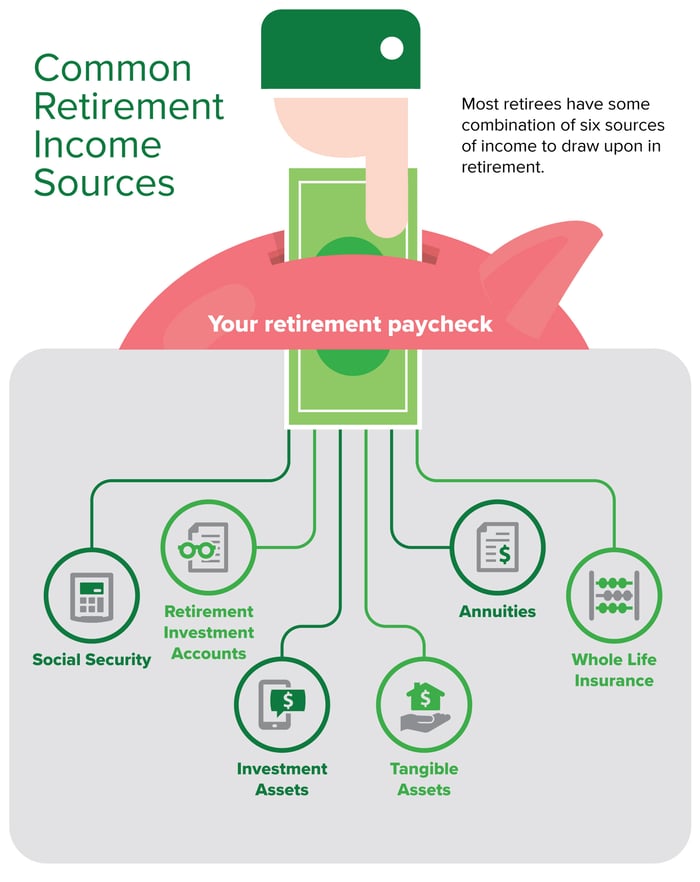

What are the typical sources of income in this phase?

Not all retirement income is equal. Some you’re required to take. Others carry tax consequences. So it’s important to know how to structure the order of your retirement income.

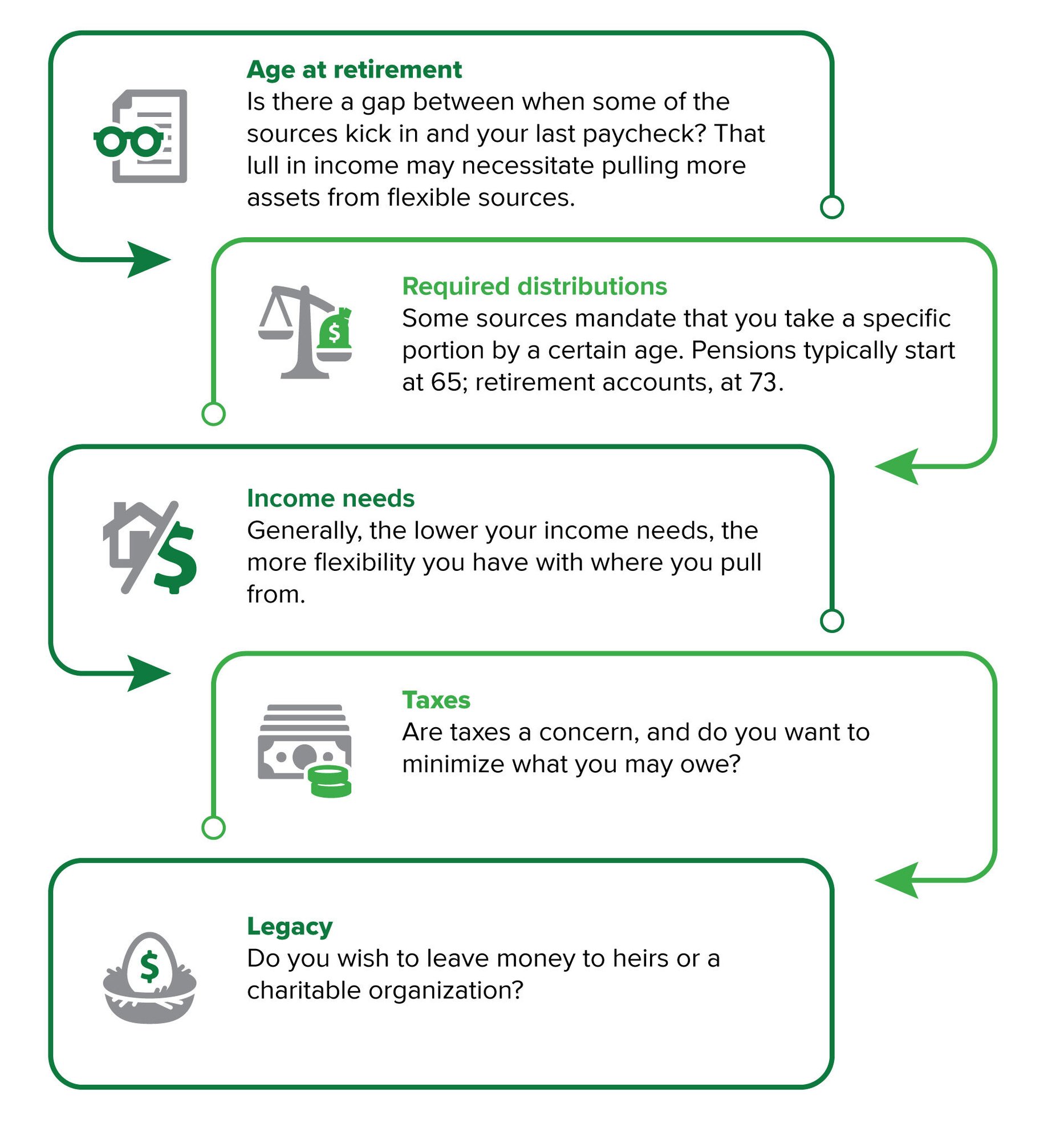

How do you know which income source to take, and at what time? The answer depends on five factors:

These five factors are a starting point to determine how much flexibility you can take on. Unless you need the income right now, here are a few sample strategies to illustrate the kind of decisions you could make if you want more flexibility and tax efficiency:

- Delay Social Security: Even though you can access it at age 62, wait to receive it. Your future monthly benefits increase 8% every year you wait from full retirement age (age 66 or 67) until 70.4

- Avoid required minimum distributions (RMDs): Convert prior to age 73 or gift them via a qualified charitable distribution. We’ll talk more about these options later.

- Cash out your pension: Consider a lump sum payout. Reinvest it in an IRA to control your income flow. You’ll still need to take annual RMDs eventually, but there may be a Roth conversion option if you don’t need them.

- Get rid of your annuities: Sell on the secondary market. Convert your annuity from a fixed-income stream to a lump sum cash option. But, beware: You won’t receive the full cash value—it’s usually discounted 10%–20%, so consult with your annuity professional.

Where does cash fit in?

We recommend setting aside three to five years’ worth of savings in a liquid account (money market or short-term government bonds) so that if the stock market drops, you don’t have to worry about your near-term income needs or be forced to sell stocks at fire-sale prices.

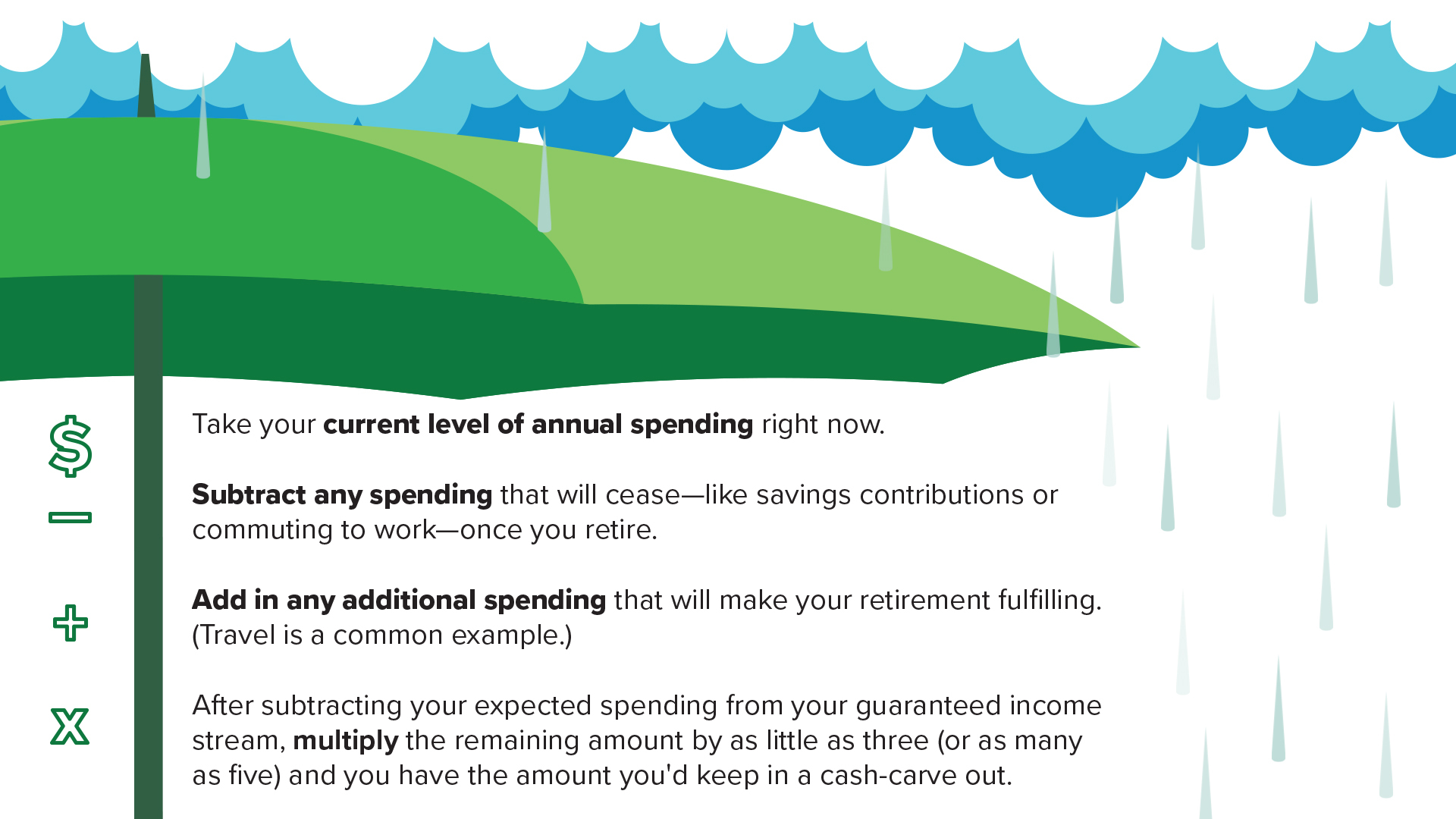

Calculating your “cash carve-out” takes a little work, but here’s a way to arrive at a number that may be appropriate for your needs and goals.

Start by considering your income streams. Determine what is guaranteed or reliable income, like a pension or Social Security. Follow the steps below to determine how much cash you need in excess of this reliable, stable income.

For example, if your spending budget is $100K per year, and you receive $60K in pension income, then your cash carve-out per year should cover the remaining $40K. To keep five years’ worth in a rainy day fund, you would need $200K ($40K x 5 years).

Okay, now that we’ve set the stage, let’s dive into our nine savvy tax moves for retirement. We break these into two categories: 1. Getting a “tax bargain” on your income and 2. Getting a “bang for your buck” through deductions, credits, and legacy planning.

| 9 Savvy Tax Moves for Retirement | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Tax Bargain on Income | Bang for your Buck | ||

| 02Income Tax on Earnings & RMDs | 03Tax on Investment Income | 04Deductions and Credits | 05Legacy Planning |

| Move #1 Time, eliminate & distribute RMDs |

Move #2 Avoid short-term capital gains |

Move #4 Bunch cash gifts |

Move #7 Choose account types |

| Move #3 Match gains with losses |

Move #5 Give appreciated securities |

Move #8 Shield wealth |

|

| Move #6 Combinations |

Move #9 Two-for-one |

||

Income Tax on Earnings and RMDs

Income Tax on Earnings and RMDs

Dear IRS, I am writing to you to cancel my subscription. Please remove my name from your mailing list. Snoopy

Snoopy

Which retirement income is taxed?

The answer is simple: Almost all of it!

Social Security

The federal government taxes up to 85% of your Social Security benefit each year. The taxable amount depends on your combined income, which you can determine by taking your adjusted gross income (AGI) plus non-taxed (tax-exempt) interest income and half of your Social Security benefits.

The taxable amount of Social Security based on your combined income is:

| Individual | Married filing jointly | |

|---|---|---|

| 0% | Up to $25,000 | Up to $32,000 |

| Up to 50% | $25,000 - $34,000 | $32,000 - $44,000 |

| Up to 85% | more than $34,000 | more than $44,000 |

Source: Social Security Administration, accessed May 27, 2025

For example, if your AGI is $10,000, you have no non-taxed interest and receive $50,000 in Social Security, then your combined income is:

$10,000 + $0 + $25,000 (i.e. ½ of $50,000) = $35,000

So as an individual, you will be taxed on 85% of your Social Security, or:

85% x $50,000 = $42,500

In addition to the federal tax, some states also tax Social Security.

Other Retirement Accounts

The most common types of retirement accounts are pensions, 401(k)s or 403(b)s, and traditional IRAs. Since these accounts are considered tax-deferred savings vehicles, you must pay tax when you receive distributions.

Again, the federal government taxes income from tax-deferred accounts—but only when you withdraw the money or take a required distribution—at the same rate as income from an employer (your ordinary income tax rate).

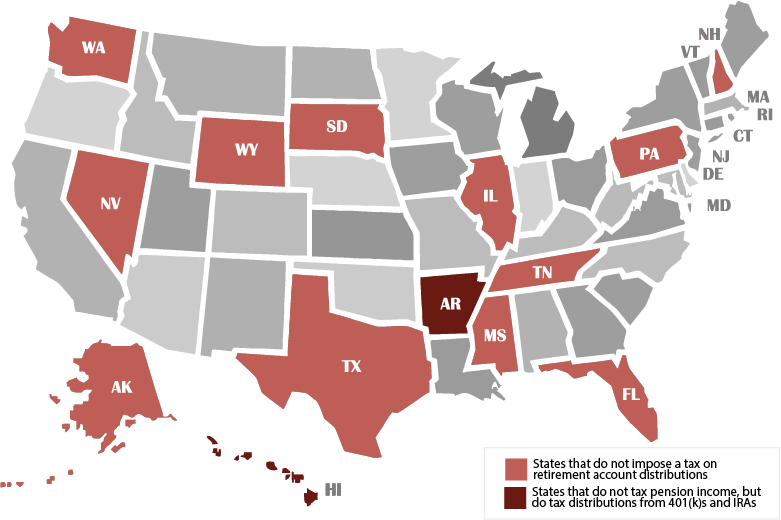

And similar to Social Security, states tax income from retirement accounts too. Almost every state imposes a tax on retirement account distributions. The exceptions are Alaska, Florida, Illinois, Iowa, Mississippi, Nevada, New Hampshire, Pennsylvania, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Washington, and Wyoming. Two other states—Hawaii and Alabama—do not tax pension income, but do tax distributions from 401(k)s and IRAs.

Taxation according to income is the most effective instrument yet devised to obtain just contribution from those best able to bear it and to avoid placing onerous burdens upon the mass of our people. Franklin Roosevelt

Franklin Roosevelt

Your income and Medicare go hand-in-hand

Medicare is a benefit for individuals aged 65 and older. It provides coverage for health care, but it’s not free. The amount you pay is on a sliding scale based on your income. Here’s how it works, and why it could potentially impact wealth planning and tax decisions.

Medicare is broken into several parts:

- Part A is hospital insurance. There’s no premium* for most people, because if you’ve worked longer than 10 years, you’ve paid Medicare taxes long enough to receive this “free” benefit.

- Part B is medical insurance. The minimum premium is $185.00 per month and can go up to $628.90 per month depending on your income.§ Find your premium here.

- Part C is Medicare Advantage. This is insurance managed by a third-party provider. This premium is based on the plan you choose.

- Part D is prescription insurance/drug coverage. The premium is based on the plan you choose and your income.

For Parts B and D, premiums are based on your income from two years prior—known as the Income-Related Monthly Adjusted Amount (IRMAA) thresholds. For instance, your 2021 income determines your 2023 premium amount. In addition, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) may change the premium. Find the 2025 premiums here.

Income considerations are important for your tax bracket and Medicare premiums. For instance, if you're pondering a Roth conversion, the amount you convert is considered taxable income in the year you convert. This income could push you into a higher income bracket, which could increase your tax rate AND your Medicare premium. For example, if you converted $100,000 two years ago, which increased your income to $350,000, your Medicare premium could be $2,662.80 more this year—from $3108 to $5,770.80.†

*No premium does not mean there is no copay or deductible.

§Married filing jointly in 2025

†Annual premium based on married filing jointly amount.

Source: CMS.gov, May 27, 2025.

Tax on Retirement Income

Strategies to minimize taxes can range from simple to complex.

- On the simple side, for example, you can move to a lower income tax state to reduce or even eliminate state tax on your earnings or retirement income. (We said simple, not necessarily desirable!)

- On the more complex side, you can manage your income to stay below the IRMAA thresholds for Medicare Parts B and D premiums, as we discussed above. In other words, the standard monthly amount covered per person is 25% of their Medicare benefits. But at the highest income level, individuals can pay 85% of their monthly Medicare benefits.

Another set of strategies focuses on decreasing or eliminating your RMDs. Many retirees plan their retirement income needs around their spending level. Some may have just enough saved to live comfortably, while others have plans to leave a legacy. Regardless of which bucket you may fall into, paying taxes is likely not high on your list of ways to spend your money!

But, the government will find a way to get its money. That’s why pension funds have a specified start date and you’re mandated to take a certain amount of distributions from your 401(k)s and traditional IRAs each year. And unfortunately, even if you don’t need the money, you must take it and get taxed on it.

Despite being required to take them, there are ways to lower your distributions and thus reduce the amount of tax you pay.

And that brings us to our first savvy move...

Some taxpayers close their eyes, some stop their ears, some shut their mouths, but all pay through the nose. Evan Esar

Evan Esar

Savvy Tax Move #1

Time, eliminate, & distribute your RMDs

Time your RMDs and other income

The IRS doesn’t care when or how often you take distributions to satisfy your RMDs—as long as you withdraw the appropriate amount by Dec. 31 each year. There’s one exception: You can wait to take your first distribution until April 1 of your 74th year. This is important because if you have a large income event in your 73rd year, you may decide to wait until the next year so your income tax rate is lower. And vice versa: If you have a liquidity event in your 74th year, you can take your RMD in your 73rd year instead.

A word of caution—if you choose to wait until the next calendar year to take your first RMD, you’ll have to receive another before the end of the same year. That’s double the distribution amount (and thus higher taxes owed) in one year.

Additionally, if you need more income than your RMD provides, consider drawing upon other income sources so you don’t jump to the next tax bracket. For instance, if your ordinary income rate is higher than the long-term capital gains rates, you may wish to generate income by selling appreciated long-term securities. Or consider ways to use tax losses from investments to offset gains and other income.

Eliminate your RMDs

Individuals who don’t need their RMDs can eliminate all or part of them by converting their retirement accounts to a Roth. Roth accounts don't pay tax on distributions—whether it’s a withdrawal of your contribution or the appreciation on your money. In other words, after contributing after-tax money, Roths can potentially grow tax-free for your entire life.

And, notably, there are no RMDs from your own Roth accounts. So that means when someone converts from a traditional to Roth IRA and pays tax on the converted amount (in the year of the switch), they’re done paying tax on those funds and any gains from those funds—FOREVER!

Let’s walk through hypothetical illustrations with two different goals.

Goal #1: Minimize taxes, no legacy

Devin and Sammy, a 64-year-old married Florida couple, just retired after selling their business for $1.6 million. They are working with their Wealth Advisor on a retirement budget. In addition to the proceeds from the sale, they have a $1.75 million traditional IRA. Here are the details of their plan. They:

Devin and Sammy, a 64-year-old married Florida couple, just retired after selling their business for $1.6 million. They are working with their Wealth Advisor on a retirement budget. In addition to the proceeds from the sale, they have a $1.75 million traditional IRA. Here are the details of their plan. They:

- feel confident they can live on $100K per year

- have enough money to cover this annual spend, so they don’t plan to take Social Security until age 70

- are not interested in leaving a legacy at this time

They asked their Advisor how they can reduce their taxes on their income from Social Security and their RMDs from their traditional IRA when they need to take them.

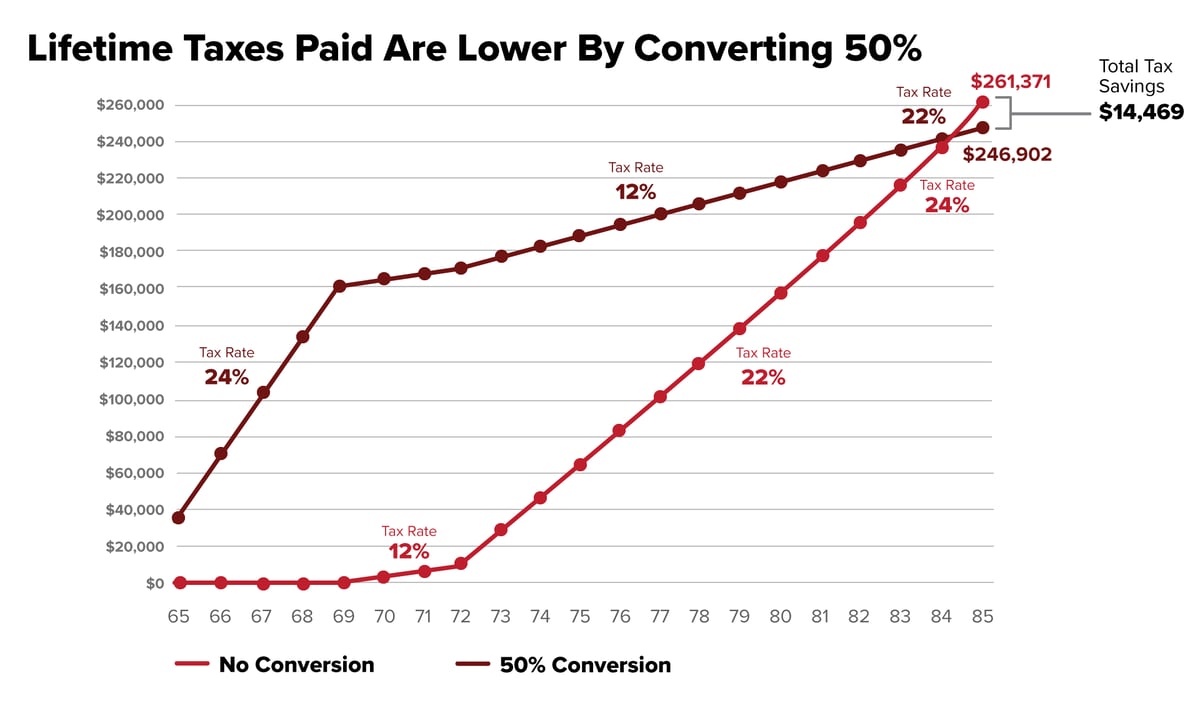

Their Advisor suggested a Roth conversion. Her analysis shows they should convert no more than 50% of the $1.75 million to a Roth, spreading the conversion over the next five years when their income tax rate should be lowest—a tax bracket trough—since they’ll have no other income until Social Security kicks in.

Calculations by Motley Fool Wealth Management. Married couple filing jointly. Total taxes paid is discounted at 2.5% to today's dollars through age 85. Maximum tax rate excludes tax rate on transfer to heirs. Assumes traditional IRA is invested in a balanced portfolio that delivers a market return of 5.38% from ages 63-70, then 4.72% return through age 85. Taxable income starting at age 70 from Social Security ($75,000 per year) excludes the 15% of Social Security not taxed. Past performance is not indication of future results. For illustrative purposes only.

In both scenarios, Devin and Sammy pay taxes of $273,380 on the initial sale of the business (income of $1,600,000 less the standard deduction of $27,700 = $1,572,300). The differences start at age 65:

- No conversion: Over the next five years (ages 65-69), they have no income and pay no income tax. At age 70, their tax rate would only be 12% through age 73 when their RMDs kick in. From ages 73 through 82, their tax rate would be 22%, then kick up to 24% through age 85.

- Convert 50%: Over the next five years (ages 65-69), their income tax rate will be 24% on the amount they convert. Then it would fall to 12% through age 83. After that, it would go up to 22%.

When asked about converting more, the analysis shows that shifting more than 50% would generate higher taxes paid than not converting at all, which is contrary to their goal.

Goal #2: Minimize taxes, leave a legacy, and increase annual cash available

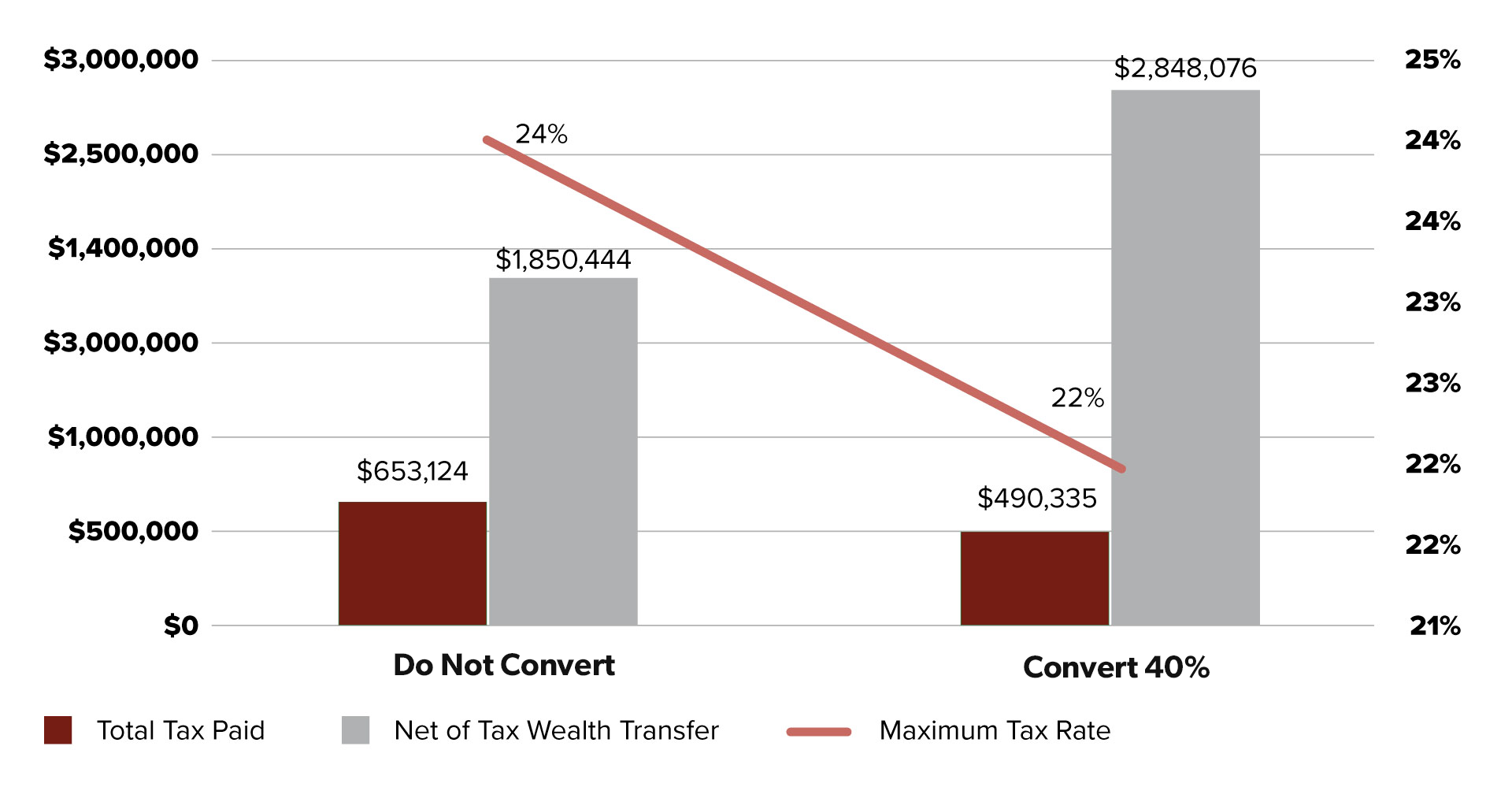

After careful consideration, Devin and Sammy decide they want to both lower their taxes and maximize the amount they can leave for heirs. But they’re also concerned about rising health care costs in their 80s and want to make sure they have at least $125K available each year during those years.

In this case, their Advisor suggested a 40% conversion. Like the 50% conversion, their taxes would be lower than not converting at all. In addition, Devin and Sammy would confidently have the desired $125K available each year in their 80s from their Social Security benefits and the non-converted portion (60%) of their RMDs without dipping into their Roth savings. (If they do not convert, they would also have sufficient funds to meet their desired $125K, but if they convert 50%, they would only have between $115K-$122K each year and may need to dip into their Roth savings.)

Finally, they would be able to leave nearly $1 million more—$2.85 million vs. $1.85 million—to their heirs than if they did not convert. And even more importantly, almost all—$2.1 million out of the $2.8 million—will be in a Roth, so their heirs likely will never have to pay taxes on the inherited amount. If they don’t convert, their heirs will need to withdraw the inherited IRA over 10 years (same time frame as a Roth) AND pay taxes on the full amount.

Do not convert vs. Convert 40%

Calculations by Motley Fool Wealth Management. *Discounted at 2.5% to today's dollars through age 85. Does not include a hypothetical/assumed 30% tax on inherited amount. **Excludes tax rate on transfer to heirs. Assumes traditional IRA is invested in a balanced portfolio that delivers a market return of 5.38% from ages 63-70, then 4.72% return through age 85. Past performance is not indication of future results. For illustrative purposes only.

Distribute your RMDs

Instead of donating cash or an appreciated security, you can give your RMDs from your retirement accounts to a cause you care about. This qualified charitable distribution (QCD) could make sense if you…

- would like to donate to charity during your life, or

- will not need your full RMD to support your living expenses, or

- do not have heirs, or do not prioritize leaving money to heirs.

QCDs are gifts to qualified public charities that, when done correctly, count toward your RMD each year. And more importantly, QCDs cancel out any tax you would have to pay on the RMD.

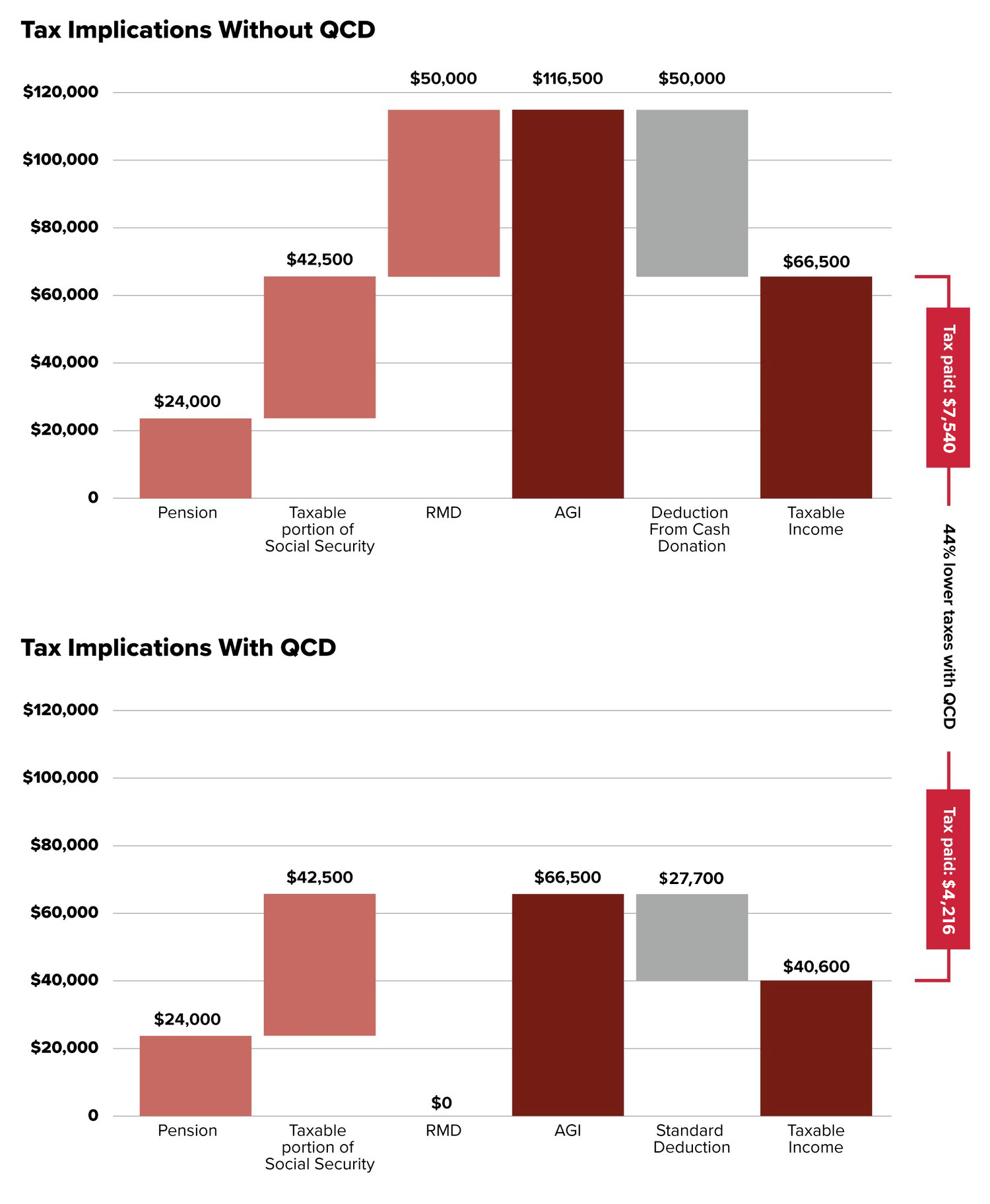

Let's take another example—Joe and Corinne, a retired couple weighing their options on making a $50K donation to their favorite charity. They planned on gifting cash, but their Wealth Advisor explained there could be a better way.

Let’s say they file their taxes jointly. They have a combined annual income of $24K from a pension, $50K in Social Security income (of which 85%, or $42,500, is taxable), and $50K of RMDs. Remember, RMDs are considered income and taxed at ordinary income rates.

Their Advisor computed two scenarios:

- Withdrawing their RMD, making a cash donation of $50K, and taking it as an itemized deduction on their tax return

- Making a QCD of $50K and taking a standard tax deduction

Here are the results of her analysis:

Source: Motley Fool Wealth Management. This analysis is hypothetical and for illustrative purposes only. For guidance and advice on taxes, consult your tax professional.

In both scenarios, Joe and Corinne gifted $50K to their favorite charity. But by making the QCD instead of a cash donation and taking the standard deduction, Joe and Corinne lowered their taxable income by the amount of the standard deduction, $27,700, resulting in paying $3,324 less in taxes—a 44% reduction.

There’s another important consideration: health care costs. (Yup, this again!) Making a QCD that reduces taxable income may mitigate exposure to Medicare Parts B and D income limits. In other words, the lower your income, the less you pay in Medicare premiums. So a potential benefit of making a QCD instead of taking an RMD is it may reduce the amount you pay for health care each year.

Of course, these decisions involve your individual tax situation, so always consult with your tax professional.

Tax on Investment Income

Tax on Investment Income

If you have a taxable brokerage account, then at some point you’ll probably want to sell some of your winners. And of course, you’ll get taxed on that investment gain.

So here are two savvy moves to lessen the blow.

Savvy Tax Move #2

Avoid Short-term Capital Gains

The first of the two moves is perhaps the simplest to implement, but at times could be emotionally challenging. Why is it an emotional decision? Because often, investors make up their minds to sell and want to do it right away. But long-term capital gains are preferable to short-term ones, AND you need to hold your investments for more than one year to avoid short-term capital gains.

Tax rates for long-term capital gains are 0%–20%, whereas short-term capital gains rates are 10%–37%, the same rate as ordinary income. For example, if you and your spouse have $500K in capital gains, you would much prefer to be taxed 15% than 35%!

Let’s walk through a hypothetical example to put this in perspective.

Let’s walk through a hypothetical example to put this in perspective.

Larry and June are considering selling two stocks. They've held Stock A for 11 months and Stock B for 13 months. They’ll recognize a $100K capital gain on each of them. How does their after-tax profit differ?

Short- vs. Long-term Gain Example

| Stock A | Stock B | |

|---|---|---|

| Holding Period | 11 months | 13 months |

| Initial Investment | $500,000 | $500,000 |

| Gain | $100,000 | $100,000 |

| Tax Bracket | 32% | 15% |

| Tax on Gain | $32,000 | $15,000 |

| After-tax profit | $68,000 | $85,000 |

| Annualized pre-tax return | 21.9% | 18.4% |

| Annualized after-tax return | 14.9% | 15.6% |

Difference in after-tax profit: $17,000

Source: Motley Fool Wealth Management. For illustrative purposes. Illustration is for a married couple filing jointly with annual income of $400K. Analysis ignores the net investment income tax, which would add a 3.8% charge on investment income in both scenarios.

By waiting just two months, (assuming that the capital gain is equal for illustrative purposes), Larry and June would keep an extra $17,000 of the investment profit. Said a different way, they would put 17% more of their profit in their pockets instead of paying it to the government!

You don’t pay taxes–they take taxes. Chris Rock

Chris Rock

Savvy Tax Move #3

Match Gains with Losses

No one likes to sell their investments at a loss. But if you no longer believe in the company you invested in or want to hold fewer shares, then selling it at a loss can help offset gains from a tax perspective. This process is commonly known as tax-loss harvesting.

So you not only remove a stock from your portfolio that you no longer want, but you can also help offset the tax on the sale of an appreciated security. Here’s an illustration of how it can work:

Matthew and Kelly want to reduce their exposure to Z company but are worried about the tax consequence of realizing the stock’s gain. They recently sold Stock Y for a loss. Their Advisor sent them the following analysis to show how they can sell some of their shares in Stock Z and not pay any capital gains tax.

Tax-Loss Harvesting Example

| Stock Y | Stock Z | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Action | Cost | Action | Cost |

| 2018 | Bought 100 shares for $200/share | $20,000 | Bought 100 shares for $50/share | $5,000 |

| 2021 | Sold 100 shares for $100/share | $100,000 | Sold 75 shares for $200/share | $15,000 |

| Total Gain (Loss) | ($10,000) | $10,000 | ||

% Gain Offset: 100% Total Taxes Paid $0

Source: Motley Fool Wealth Management. For illustrative purposes only.

Since they recognized a loss of $10,000 when they sold Stock Y, they can sell 75 shares of Stock Z at the market price of $200/share for a gain of $10,000. Because the capital gain equals the realized loss, they should pay zero tax.

Furthermore, if their realized loss was even greater than the $10,000 capital gain—let’s say they realized $13,000 in losses—Matthew and Kelly could use $10,000 of the realized loss to offset their $10,000 capital gains AND up to $3,000, or their remaining net losses, against other income. This can be a way to use realized losses more efficiently against ordinary income, such as wages, which, as we said, are typically taxed at a higher rate.

What do you do with a large, concentrated stock position?

Were you lucky enough to buy Apple stock (AAPL)* on April 8, 1983 for $0.18 and, more impressively, still hold it?

Or did you receive stock options from Microsoft (MSFT)* in the early 1990s for $1 a share?

While these are good problems to have—Taylor Swift would say “Champagne Problems”—they potentially leave you with a large tax bill when you sell them. So how should you handle a large, appreciated stock position?

There’s no easy solution around selling it while you’re alive and not paying long-term capital gains tax. Sure, you could employ various hedging strategies with over-the-counter derivatives to potentially reduce your equity risk. Similarly, you could participate in an equity exchange fund to diversify the holding. But neither of these solves the tax problem.

So what could you do? Employ the solutions we already discussed. For example, you could offset gains with losses by tax-loss harvesting over time. Or you could gift shares to family or charity. In addition, you could leave it in your estate so that when you pass, the shares step up in cost basis and become a tax-efficient wealth transfer.

Another solution is to evaluate and trim the position each year, putting the sale proceeds into a diversified portfolio. Look at it this way: You only need to get rich once! So by diversifying a substantial gain, you can hopefully "stay rich."

This annual evaluation would occur at the end of the year, so your Wealth Advisor could most accurately determine your capacity for additional income after accounting for other income throughout the year and potential tax-loss harvesting opportunities.

Deductions and Credits

Deductions and Credits

The best things in life are tax free. Joseph Bonkowski

Joseph Bonkowski

Eighty-seven percent of taxpayers take the standard deduction on their tax return, primarily because their home is either paid off, or other restrictions reduce the amount of write-offs available.5 But if you are able to itemize your deductions—with things like charitable donations, for instance—you may be able to push your tax bracket lower. For example, combined federal plus state tax rates can be upwards of 50% at the highest tax bracket. So if you can deduct your charitable gifts, every dollar you contribute to a charity could provide you a $0.50 tax benefit at that 50% tax bracket—a pretty good deal!

Conversely, the effective tax rate at the lowest bracket is roughly 10% (depending on state taxes), which means every dollar you contribute to a charity could provide you a $0.10 tax benefit—not as great a deal. So you see, it’s important to be mindful of how much you want to donate in order to lower your AGI, but to remain in the tax bracket that earns you the greatest benefit overall. HINT: It comes down to savvy moves #4, #5, and #6.

Savvy Tax Move #4

Bunch Cash Gifts

Let’s walk through a hypothetical example.

Sam and Veronica wish to make annual donations of 10% of their gross income— $27,500—to charity each year. Their Advisor suggested that bunching their gifts may make more sense. She ran the following analysis to show the impact.

Bunching Cash Gifts Example

| Scenario 1 | Scenario 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year 1 Standard Deduction |

Year 2 Standard Deduction |

Year 1 $55,000 |

Year 2 Standard Deduction |

|

| Total Income | $275,000 | $275,000 | $275,000 | $275,000 |

| Charitable Contributions | ($27,500) | ($27,500) | ($55,000) | $0 |

| Applicable Deductions | ($27,700) | ($27,700) | ($55,000) | ($27,700) |

| Tax Paid | $46,152 | $46,152 | $39,600 | $46,152 |

| Taxes Paid Over Two Years | $92,304 | $85,752 | ||

| Effective Tax Rate Over Two Years* | 17% | 16% | ||

Tax Savings from Bunching: $6,552

Assumptions: Gross annual earnings for couple $275,000. Desired charitable contributions $27,500. Married filing jointly tax rate of 24%, graduated for income.

This example shows the potential benefits of lumping charitable gifts into one year rather than spreading them out over time.

In Scenario 1, Sam and Veronica’s annual donation of $27,500 was less than the standard deduction of $27,700. As such, they took the standard deduction on their tax return each year, resulting in a two-year effective tax rate of 17%.

In Scenario 1, Sam and Veronica’s annual donation of $27,500 was less than the standard deduction of $27,700. As such, they took the standard deduction on their tax return each year, resulting in a two-year effective tax rate of 17%.- Alternatively, in Scenario 2, Sam and Veronica’s gift of $55,000 exceeded the standard deduction in year 1, so they were able to write off the full amount on their taxes. In year 2, even though they did not make a charitable contribution, they were still able to take the standard deduction. Because of this bunching strategy, their two-year effective tax rate was 16%.

The result: While a 1% difference in tax rate seems minimal, Sam and Veronica saved $6,552 over the two years by bunching their gifts in one year. That's a 7.1% tax savings. And the charity still received the same amount, $55,000.

However, if they were concerned about the “lumpiness” of their gift, they could open and contribute the $55,000 to a donor-advised fund (DAF). That way, they could benefit from a lower effective tax rate (Scenario 2) and distribute the funds from the DAF annually—a win-win.

Savvy Tax Move #5

Give Appreciated Securities

There are also excellent tax advantages for giving noncash contributions, and the impact may be greater than a cash donation. In other words, when you have a security that has appreciated considerably over a holding period of one year or more, you can donate that security to a qualified charity and receive a charitable income tax deduction for the security’s fair market value. This means you can reduce your income and incur a lower tax bill as a result. In addition, when you donate an appreciated security, you can avoid the capital gains tax you otherwise would have to pay if you sold it for the gain.

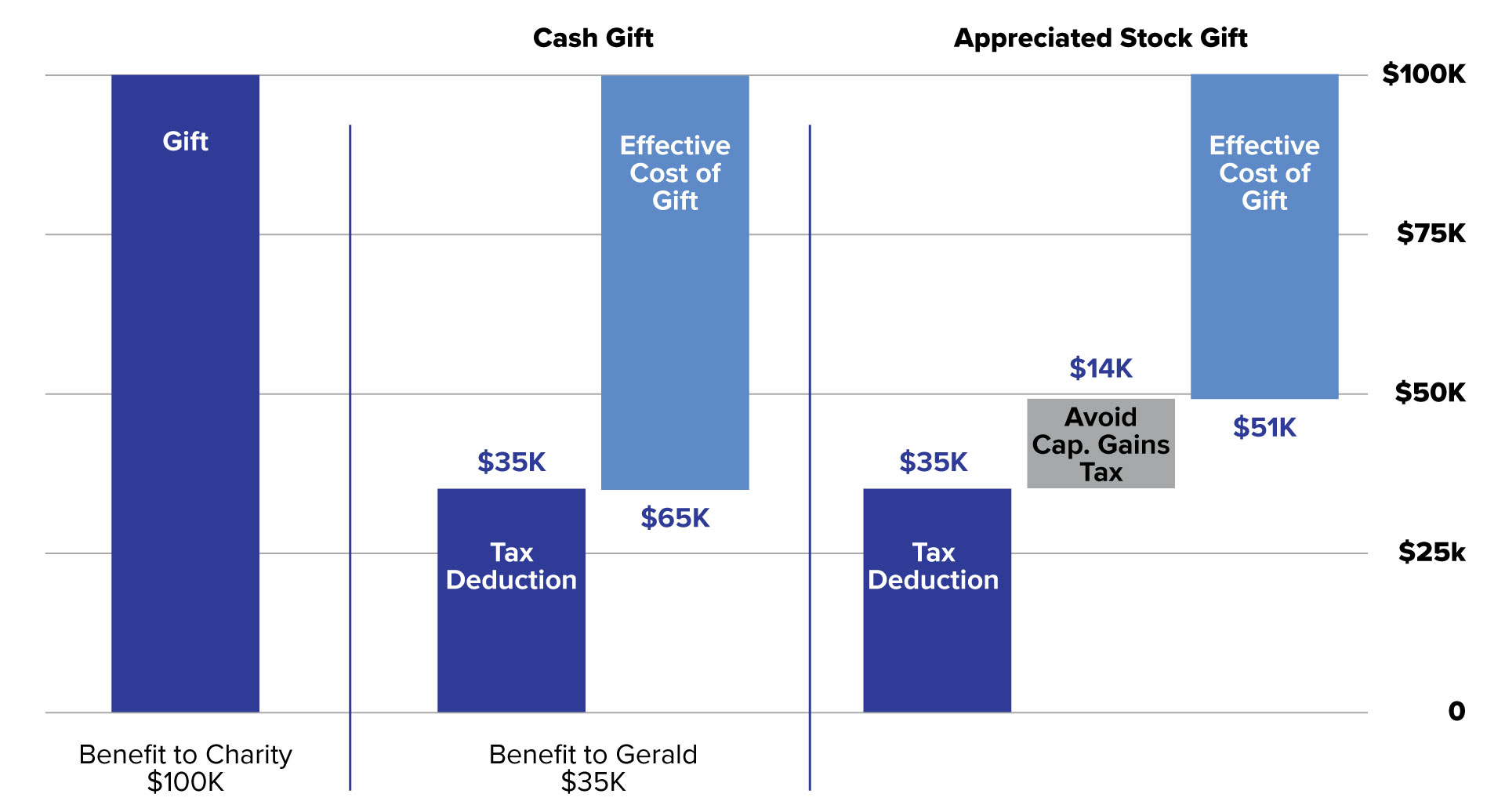

So how do you know if you should donate cash or an appreciated security? Gerald, in our next example, is facing this dilemma:

He would like to give to a charity in his mom’s name and is weighing the trade-off between gifting cash or an appreciated security. Here’s the analysis his Advisor showed him:

Tax Benefit of Cash vs. Stock Gift

For illustrative purposes only. Gift to qualified public charity. Federal tax rate: 35%. Long-term capital gains rate: 20%. Stock basis: 30%.

If Gerald makes a $100,000 cash donation, it could result in a charitable tax benefit of $35,000, effectively lowering the cost of the gift to $65,000. But by donating a security, Gerald can take the charitable tax deduction ($35,000) plus the benefit of not having to pay tax on the stock’s appreciation ($14,000), for a total effective gift cost of ($51,000). And if Gerald still wanted to hold that security in his portfolio—because he transferred and did not sell it—he can use the $100,000 of cash he has set aside for a cash donation and repurchase the security immediately, thus resetting his cost basis.

The politicians say ‘we’ can’t afford a tax cut. Maybe we can’t afford the politicians. Steve Forbes

Steve Forbes

Savvy Tax Move #6

Combinations

Sometimes, more than one strategy may make sense, but combining several may offer the best tax advantage. For example, you could pair tax-loss harvesting with donating to charity. So, after you sell a security at a loss to offset the capital gain from another sale, you could donate the cash to potentially receive a charitable deduction up to 60% of AGI.

Interested in offsetting the tax from a Roth conversion? At the same time you shift assets from a traditional to Roth IRA, donate an appreciated security that equals the conversion amount to charity. That way, the tax deduction from the donation should offset the amount of tax on the conversion, leaving you with a $0 tax liability.

Of course, all the strategies we discuss in this section are subject to IRS rules and limitations, so as always, we recommend you consult your tax professional and Wealth Advisor for guidance.

Sunsetting of Tax Cuts and Jobs Act Benefits

A total of 23 individual and business tax provisions from the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) expire Dec. 31, 2025. Here are some of the more common provisions that are expected to change or go away completely unless it is renewed:

Negative impacts from sunsetting TCJA benefits

- The lower tax rates and brackets for individuals and trusts and estates may rise. Current individual rates: 10%, 12%, 22%, 24%, 32%, 35%, and 37%. Current trust and estate rates: 10%, 24%, 35%, and 37%.

- The standard deduction could fall by half

- “Excess business loss” carryforwards may be reduced or disappear

- Child tax credit may halve

- Charitable contribution deduction limitation increased to 60% of AGI and carryforwards allowed for up to five years may go back to 50%

- Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT) higher exemption amounts may lower, hitting more taxpayers

- Estate and gift tax exemption amount that nearly doubled may be cut in half

- New deduction for pass-through income could disappear

Positive impacts from sunsetting TCJA benefits

- State and local tax deduction that is limited to $10K (married filing jointly) may go back to no cap

- The limited mortgage & home equity indebtedness interest deduction may be expanded

- Return of miscellaneous deductions (including investment management fees) that exceed 2% of AGI

- Personal exemption may rise from $0 back to $4K

Why is it important to prepare for these potential changes to the tax code?

Knowing when these exemptions or deductions may go away allows you to plan ahead. For example, if you want to gift to charity or heirs, you may consider transferring wealth before the gift and estate lifetime exclusion amount changes. Or, you may want to start a donor-advised fund and bunch several years of charitable gifts now. That way, you can itemize and get a larger deduction now, then take the higher standard deduction over the next few years until it sunsets.

Source: mlrpc.com, Jan. 11, 2018

The purpose of a tax cut is to leave more money where it belongs: in the hands of the working men and working women who earned it in the first place. Bob Dole

Bob Dole

Legacy Planning

Legacy Planning

Philosophy teaches a man that he can't take it with him; taxes teach him he can't leave it behind either. Mignon McLaughlin

Mignon McLaughlin

Do you plan to leave money to your kids, grandbabies, or charity?

If you want more control over when and how your wealth is disbursed and spent, you need a legacy plan. A legacy plan includes savvy moves to structure and shield wealth from tax.

Savvy Tax Move #7

Choose Account Type

Many people use trusts for legacy planning. They work like this: A grantor (trust maker) places assets—like cash, stocks, bonds, or real estate deeds—in an account to be managed by a trustee according to guidelines established by the grantor for named beneficiaries.

When a grantor dies, beneficiaries do not immediately incur taxes for assets still held in the trust, as these trusts pay their own tax on assets they hold. But they distribute trust income annually to beneficiaries (as a conduit entity), which beneficiaries must pay tax on. When assets such as stocks and real estate are held in a trust (depending on the type), the current market value at the time of death usually becomes the asset's cost basis for beneficiaries.

There are many kinds of trusts. Testamentary trusts are activated by a will, while living trusts are created while the grantor is alive. Living trusts can be either revocable or irrevocable, but after the grantor’s death, all trusts become irrevocable.

The taxation of trusts is complex, so it always makes sense to consult a tax professional. While they potentially can be effective in reducing estate tax exposure upon wealth transfer, they may not be the best structure. For instance, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 made trusts inefficient for capital gains.

The avoidance of taxes is the only intellectual pursuit that carries any reward." John Maynard Keynes

John Maynard Keynes

Savvy Tax Move #8

Shield Wealth

The federal government and some states tax estates and gifts. For estates above the lifetime exclusion of $12.92 million, the assets that are not shielded (using trusts, for example) are taxed at 40% of their current value. That means an estate currently valued at $13.92 million could have $1 million that is taxable at 40%, resulting in a $400K tax bill. However, there are many nuances to the lifetime exclusion and the annual gift exclusion that can influence if and how you may choose to parse your estate.

Legacy planning can uncover various ways to reduce this tax. For instance, if you are married, a simple tactic is to make sure your spouse is set as your primary beneficiary to preserve the stretch treatment of an inherited traditional IRA.

The reason why preserving the stretch treatment is important is because otherwise, distributions from an inherited traditional IRA would need to be taken within 10 years of your passing. And just like when you make withdrawals from your IRA, your spouse will have to pay ordinary income tax on that money. But with a stretch, a surviving spouse may roll the IRA into their own, which calculates RMD withdrawals based on your spouse's life expectancy. This may stretch out the IRA distributions and potential benefits of tax-deferred growth.

Another maneuver is to take advantage of annual gifting limits to reduce your taxable estate upon your death. This year, each taxpayer can gift $19,000 per person without triggering a gift tax. But if you exceed the annual amount, you don't have to pay gift tax unless the total amount over the course of your life exceeds the lifetime gift tax limit for that year.

However, this planning opportunity may go away soon. The lifetime gift tax exclusion is scheduled to be cut in half in 2026—to roughly $6.8 million. But if you make large gifts before 2026, you don't lose the benefits of the higher gift tax exclusion amount after it's lowered.

Additionally, you may choose to give money to heirs while you’re still living to reduce your taxable estate. Here are some reasons for and against gifting while you’re alive.

When should you gift?

| Reasons to gift while you're alive | Reasons to wait to gift until you pass |

|---|---|

| It can be very rewarding to watch your heirs enjoy their inheritance. You can help your loved ones build financial security or pay for major expenses like college. | If you don't think your estate will have a value in excess of the lifetime exclusion, there likely won't be any taxable benefit to giving your money away early. |

| Utilizing the annual gift tax exclusions strategically can lower the value of your taxable estate. | If you plan to give investments to your heirs, it can be beneficial from a long-term tax planning perspective to wait. Assets such as stocks receive a step up in basis upon death and can result in significant capital gains tax savings. On the other hand, assets given during life keep the same cost basis that the original owner paid. |

| Giving money to your favorite charities while you're alive can reduce your estate's value even more and get you valuable income tax deductions each year in the process. | When giving away your assets while you're alive, it's important to consider whether you're keeping enough of a financial cushion for yourself for unplanned expenses, such as long-term care. |

| The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act doubled the lifetime exclusion, so if you're worried about it reverting back to previous levels after 2025, you can give away your money now to take advantage of the higher amount. | Gifting can complicate your tax filings. Even if you don't end up owing taxes on your gifts, you will still need to report the money you've given beyond the annual exclusion. |

Savvy Tax Move #9

Two-For-One

What about a planning tool that combines income needs with legacy?

A charitable gift annuity (CGA) can do just that, by killing two birds with one stone so to speak. A CGA provides lifetime income and charitable giving. It works like this:

A charitable gift annuity is a contract between you, the donor, and a charity. After you make a sizable gift to charity—in the form of cash, securities, or another acceptable asset—you receive a fixed stream of income from the charity for the rest of your life. Once you pass, the remainder of the gift goes to the charity. In addition, you receive a tax deduction for the estimated portion of the gift that will eventually go to the charity.

A similar option is a charitable remainder trust (CRT). Like a CGA, CRTs provide income during your life, but instead of the charity being responsible for annual distributions, the trustee is responsible. CRT's are irrevocable trusts—meaning once the gifts are made and assets transferred, they are owned by the trust not the person. Payments from a charitable remainder trust to the donor are taxable and must be reported as income or capital gains. The donor also gets a tax deduction that is limited to the present value of the charitable organization's remainder interest. This is calculated as the value of the donated property minus the present value of the annuity.7

How do you know if you should use a CRT or a CGA? A CRT can be more appropriate than a CGA for folks that want to leave money to a smaller charity, or who want to have greater control around the underlying investment selections and payouts (options are unitrust where payouts fluctuate with actual income generated, or annuity where the payout amount is consistent over time).

Legacy planning can help you with charitable giving

If you're contemplating giving some of your wealth to charity, you may want to consider a donor-advised fund (DAF) or a family foundation.

A family foundation gives you complete control of how your money is donated. But it is complicated to set up and maintain.

On the other hand, DAFs are easy to establish and are managed by professional organizations, such as community foundations or large brokerages. Once donors contribute assets to the DAF, they are the property of the DAF, and the DAF donates them to a specific charity.

DAFs have become a popular means of charitable giving in recent years due to their ease of use, attracting people of vastly different financial means. DAFs now hold over $250 billion in assets earmarked for charities.6 In addition, donors receive an immediate tax deduction for the donation. DAFs also offer more privacy than family foundations.

Isn’t it appropriate that the month of the tax begins with April Fool’s Day and ends with cries of ‘May Day!’? George William Curtis

George William Curtis

Footnotes and Disclosures:

1 Tax Foundation, accessed May 27, 2025.

2 IRS.com. Internal Revenue Code § 1.61-1(a). Accessed May 27, 2025.

3 irs.gov, accessed May 27, 2025.

4 Social Security Administration, "Delayed Retirement Credits." Accessed May 27, 2025.

5 IRS.gov. Statistics through 2019 FY, revised Oct. 2020. Accessed May 27, 2025.

6 nptrust.org, 2024 DAF Report. Accessed May 27, 2025.

7 IRS.gov. Accessed May 27, 2025.

*All information presented herein is for informational purposes only and should not be deemed as investment advice or a recommendation to purchase or sell any specific security. The securities identified and described in this article do not necessarily represent the securities purchased or sold for our portfolios. You should not assume that an investment in these securities was or will be profitable, and there is no assurance, as of the date of this presentation, that the securities have been or will be in any model portfolio. All information expressed in this article is subject to change without notice. There is no representation or guarantee that any opinion, estimate or projection will be realized. The information is believed to be reliable at the time of publication of this article in May 2025; however no representation or warranty is made concerning its accuracy. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. All investments involve risk and may lose money (including principal).

This report is provided for informational purposes only, reflects our general views on investing and should not be relied upon as recommendations or financial planning advice. We encourage you to seek personalized advice from qualified professionals, including (without limitation) tax professionals, regarding all personal finance issues. While we can counsel on tax efficiency and general tax considerations, Motley Fool Wealth Management ("MFWM") does not (and is not permitted to) provide tax or legal advice. Clients who need such advice should consult tax and legal professionals. This report may not be relied upon as personalized financial planning or tax advice.

Motley Fool Wealth Management is an SEC-registered investment advisor with a fiduciary duty that requires it to act in the best interests of clients and to place the interests of clients before its own. HOWEVER, REGISTRATION AS AN INVESTMENT ADVISOR DOES NOT IMPLY ANY LEVEL OF SKILL OR TRAINING. Access to Motley Fool Wealth Management is only available to clients pursuant to an Investment Advisory Agreement and acceptance of Motley Fool Wealth Management's Client Relationship Summary and Brochure (Form ADV, Parts 2A and 2B). You are encouraged to read these documents carefully. All investments involve risk and may lose money. Motley Fool Wealth Management does not guarantee the results of any of its advice or account management. Clients should be aware that their individual account results may not exactly match the performance of any of our Model Portfolios. Past performance is no guarantee of future results. Each Personal Portfolio is subject to an account minimum, which varies based on the strategies included in the portfolio. Motley Fool Wealth Management retains the right to revise or modify portfolios and strategies if it believes such modifications would be in the best interests of its clients.

During discussions with our Wealth Advisors, they may provide advice with respect to 401(k) and IRA rollovers into accounts that are managed by Motley Fool Wealth Management. Such recommendations pose potential conflicts of interest in that rolling retirement savings into a MFWM managed account will generate ongoing asset-based fees for Motley Fool Wealth Management that it would not otherwise receive.

Motley Fool Wealth Management, an affiliate of The Motley Fool, LLC (“TMF”), is a separate legal entity, and all financial planning advice and discretionary asset management services for our clients are made independently by the wealth advisors and asset managers at Motley Fool Wealth Management. No TMF analyst is involved in the investment decision-making or daily operations of MFWM. MFWM does not attempt to track any TMF services.

WM-1010-RP-2025-06