To print this report or save it as a PDF, click here.

The term “Roth conversion” is just about as jargon-y as you can get. But for folks who might see retirement on the horizon sometime soon, it can be a powerful planning tool for optimizing existing retirement resources.

It’s not uncommon for dutiful savers to stash away the maximum contribution in their 401(k), 403(b), or IRA for decades. While growing substantial retirement savings isn’t a problem in and of itself, having a large portion of your future retirement income be subject to required minimum distributions (RMDs) and ordinary income tax is. See, the taxman always comes knocking—and a Roth conversion can put you in greater control of when and how much to hand over at any given time.

Just as you can be strategic with timing your Social Security benefits or other retirement resources, Roth conversions are powerful planning tools for proactively reducing RMDs and creating potentially tax-free income to enjoy in retirement. As we’ll dive into more detail below, some people can even save on their lifelong tax liability by opting for a multi-year Roth conversion strategy before retirement—though this depends on quite a few factors.

Ready to learn whether a Roth conversion is right for you? Don’t worry, we’ve covered every question, tip, trick, and must-know in this in-depth guide.

Common Retirement Accounts (And How They’re Taxed)

Common Retirement Accounts (And How They’re Taxed)

Before we dive into the specifics of a Roth conversion, let’s take a step back and review the benefits and challenges of a few of the most common tax-advantaged retirement accounts available. These accounts will play important roles within the Roth conversion process, and understanding their potential advantages or drawbacks now can help you decide whether a Roth conversion is right for you.

While all the different account types may get confusing, the one thing to remember as a general rule of thumb is that you can’t outrun the IRS forever. The government will collect taxes either coming (when you first earn the money) or going (when you ultimately distribute it from tax-deferred retirement plans).

Traditional 401(k)

A traditional 401(k) is a retirement savings plan offered through your employer. It’s protected under the Employee Retirement Income Security Act (ERISA), meaning the plan is federally regulated by the U.S. Department of Labor to ensure participants’ funds are safeguarded now and well into the future.1 And while we use the term 401(k), the rules are substantially the same for many numerically-named plans such as 403(b), 457, and even TSP for federal employees.

Contributions made to a 401(k) are typically done through payroll deductions, which occur before taxes are withheld. This means they’re “pre-tax contributions,” and they reduce your overall taxable income for the year.

Depending on your employer’s plan offerings, you may have a (limited) choice in how your funds are invested within the account. Many plans offer a selection of mutual funds and/or ETFs to choose from, but don’t allow you to invest in individual stocks or funds outside of the plan offerings.

As the funds in your 401(k) grow, you won’t be required to pay taxes on the capital gains each year, even if you make trades within the account. Deferring the tax liability is certainly a benefit since your money stays invested and continues compounding between now and retirement.

Once you reach age 59.5, you’ll be allowed to make qualified withdrawals from your 401(k). Anything you withdraw, whether it’s part of your principal contributions or growth, will be taxed as ordinary income, just like your paycheck was during your earning years.

But there’s an important wrinkle: starting at age 73 (or age 75 for those born in 1965 or later), your 401(k) will be subject to Required Minimum Distributions (RMDs). Each year, you’ll be required to withdraw at least a minimum amount from the account based on the account balance at the end of the previous year and the IRS life expectancy table.2 Again, these distributions are subject to ordinary income tax.

2025 401(k) Contribution Limits3

| Age | Limit |

|---|---|

| Up to age 49: | $23,500 |

| Age 50-59: | $31,000 |

| Age 60-63: | $34,750 |

| Age 64 and over: | $31,000 |

Regardless of whether you want or need the funds, you’ll have to withdraw them and pay the associated taxes.

Traditional IRA

A traditional IRA operates very similarly to a traditional 401(k), at least tax-wise, and is also protected under ERISA. Contributions are tax-deductible, growth accumulates tax-deferred, and withdrawals are subject to ordinary income tax.

You also must wait until age 59.5 to withdraw penalty-free from your IRA, and RMDs begin at age 73 (or age 75 for those born in 1965 or later).

To be eligible to contribute to an IRA, you or your spouse must earn taxable income. It’s also important to note that if you or a spouse are covered by a workplace plan (like a 401(k)), you may not be allowed to deduct all or some of your IRA contributions depending on your adjusted gross income for the year.

Unlike a 401(k), a traditional IRA allows you to invest in mutual funds, ETFs, individual stocks, and (possibly, depending on your brokerage) some alternative investments.

Did You Know…

By the end of 2023, 60% of households with Roth IRAs also owned traditional IRAs?4 Tax diversification is key to creating a sustainable retirement income strategy.2025 IRA Contribution Limits3

| Age | Limit |

|---|---|

| Up to age 49: | $7,000 |

| Age 50 and better: | $8,000 |

Many retirees end up with a Rollover IRA, which is a specific type of Traditional IRA that is sourced from a qualified rollover from an employer plan such as a 401(k). For purposes of Roth conversion analysis, a Rollover IRA and a Traditional IRA would be treated the same.

Brokerage Account

A brokerage account is the most flexible investing tool available, although it lacks the tax advantages of retirement-specific accounts.

A taxable brokerage account is funded with “after-tax” dollars, meaning the contributions you make to your brokerage account have already been taxed. Within your brokerage account, you can invest in different asset types, including individual stocks or bonds, ETFs, mutual funds, real estate investment trusts (REITs), and other assets (depending on what’s available through your brokerage platform). For many investors, their largest after-tax asset is their personal residence.

As you sell investments for a profit or earn dividends and interest, you’ll be responsible for paying taxes on the earnings. As a reminder, earnings within a retirement account (like a 401(k) or IRA) grow tax-deferred, but that’s not the case for a brokerage account. The good news is, some of those earnings may be subject to long-term capital gains tax—which caps out at 23.8% at the federal level.5 For most investors, this will be lower than the ordinary income tax rate they’d pay with a 401(k) or traditional IRA.

Brokerage accounts are essential for long-term wealth building because, unlike retirement accounts, they’re not subject to:

- Annual contribution limits

- Income limits

- Minimum required distributions

- Age requirements

- Early withdrawal penalties

You can contribute as much as you want to your brokerage account and take withdrawals whenever you need—though you’ll likely want to follow a strategic, long-term plan for building and supporting a sustainable portfolio.

Roth Accounts

What’s in a name?

We just couldn’t resist the call of our Shakespearean roots. Roth IRA’s were brought into the tax code in 1997 as the eponymous creation of Senator William Roth, Jr. of the great state of Delaware. Since then, the Roth IRA, and its younger sibling the Roth conversion have enjoyed broad political appeal on both sides of the aisle.And that brings us to Roth accounts.

A Roth IRA or Roth 401(k) is a tax-advantaged retirement account funded with after-tax dollars (as opposed to pre-tax dollars, which is the case for traditional 401(k)s and most IRAs).

Because the money used to fund a Roth account has already been taxed, contributions to a Roth account aren’t tax-deductible. Withdrawals of principal contributions (any amount you put into the account over the years) are tax-free. If you meet certain criteria, qualifying withdrawals of earnings will be tax-free as well.

First, the account must be at least five years old. More specifically, you must have made your first contribution to the account at least five years ago.

In addition, you must meet one of the following rules:6

- You’re 59.5 or older,

- You’re disabled (following IRS guidelines),

- You’re buying your first home, or

- You inherited a loved one’s Roth account.

In addition to enjoying potentially tax-free income in retirement, your Roth account is not subject to RMDs. You’re free to allow the account to continue accumulating as long as you wish. In fact, many people find a Roth account to be a tax-effective tool for transferring wealth to loved ones as part of their estate plan.

Not everyone is eligible to contribute directly to a Roth IRA since they’re restricted by income limits. High earners with a modified adjusted gross income above the income ceiling cap may be ineligible to contribute to a Roth IRA—or limited to contributing a reduced amount.

In 2025, the income ceiling limits are:3

- Single filers and head of household: Above $165,000 ($150,000–$165,000 phase-out range)

- Married filing jointly: Above $246,000 ($236,000–$246,000 phase-out range)

Did you know…

Only 12.1% of investors 60 and older withdrew from their Roth IRAs in 2020, compared to 78.3% of traditional IRA owners?4 Without required minimum distributions, retirees can keep Roth accounts growing for the rest of their lives.Roth IRA Contribution Limits3

| Age | Limit |

|---|---|

| Up to age 49: | $7,000 |

| Age 50 and over: | $8,000 |

What Is a Roth Conversion?

Preparing for retirement means finding opportunities to minimize both your current tax bill and lifelong tax obligations so you can maximize the effectiveness of your retirement savings. To do this, you’ll likely need to establish a diverse retirement income strategy—one that’s able to capitalize on the benefits from various accounts including your 401(k), IRA, Roth accounts, and brokerage accounts.

A Roth conversion enables you to do just that. By transitioning assets that received the upfront tax benefits of a traditional 401(k) or IRA into a Roth account, you can create future tax-free retirement income.

To complete a Roth conversion, you’ll need to take the funds from your existing pre-tax retirement accounts (a 401(k) or IRA) and transition them into a Roth IRA. Since these accounts were funded with pre-tax dollars, any amount converted from a traditional to Roth account will be included as taxable income on your upcoming tax return. Because this is considered a conversion and not a withdrawal, however, you will not face an early withdrawal penalty (as long as you follow proper guidelines and instructions).

The benefit of a Roth conversion is that come age 59.5, you’ll be able to pull qualified withdrawals tax-free.

Creating essentially tax-advantaged bookends, a Roth conversion can help certain investors optimize their tax liability throughout their lifetime. Just keep in mind, the IRS will want its cut eventually. A Roth conversion is a taxable event, and you’ll need to keep that added tax liability in mind when deciding when and if this strategy is right for you.

How Roth Conversion Taxes Are Calculated

The tax due on a Roth conversion depends on the nature of the funds being converted. Pre-tax contributions and earnings from a traditional IRA or 401(k) are fully taxable when converted. However, if your account includes any post-tax (non-deductible) contributions, the IRS uses the pro-rata rule to determine how much of your conversion is taxable.

Here’s the gist: You can’t cherry-pick and convert just the post-tax money. Instead, the IRS views all your IRAs as one imaginary combined account and applies a ratio of pre-tax to post-tax dollars when calculating the taxable portion of a conversion. That means even if you’re trying to convert only post-tax contributions, a portion may still be subject to tax.

Types of Retirement Accounts

401(k) (or 403(b), 457, and TSP accounts)

Workplace defined contribution retirement plans with annual contribution limits set by the IRS. Contributions are tax-deductible, earnings grow tax-deferred, and withdrawals are subject to ordinary income tax.

Traditional IRA

An individual retirement account available to individuals with earned income and their spouses who may not have access to a workplace plan. Contributions are tax-deductible, earnings grow tax-deferred, and withdrawals are subject to ordinary income tax.

Rollover IRA

A holding account used to house previous employer 401(k)s or other IRAs. Funds maintain their tax-advantaged status, and no early withdrawal penalties are incurred.

Simplified Employee Pension (SEP) IRA

A type of IRA specifically for self-employed solopreneurs and business owners with small teams. Only the employer makes tax-deductible contributions to the account, and the annual limits are higher than traditional or Roth IRAs.

Savings Incentive Match Plan for Employees (SIMPLE) IRA

A type of IRA designed for small business owners with fewer than 100 employees. Both the employer and employees make tax-deductible contributions, which grow tax-deferred until retirement.

Roth IRA

An individual retirement account available to individuals with earned income who would like to build potentially tax-free income in retirement. Contributions are not tax-deductible, earnings grow tax-deferred, and qualified withdrawals (on both contributions and earnings) are tax-free.

Why Do a Roth Conversion?

Why Do a Roth Conversion?

A Roth conversion enables your retirement savings to reap some of the benefits of both a traditional IRA or 401(k) and a Roth account.

When you first contributed to your 401(k), you were able to deduct those contributions from your taxable income for the year. Considering how high the annual contribution limit is for 401(k)s, this benefit can yield immediate and sizable tax savings. Over time, those contributions grow tax-deferred—allowing more of your wealth to compound without interference.

But as retirement approaches, or as your annual income levels evolve, you might want to take action now to secure tax-free income in retirement. A Roth conversion allows you to convert as much or as little of your existing pre-tax resources into future tax-free income. In years when your other income sources are low, for example, it might make sense to complete a bigger Roth conversion.

Another benefit of converting funds from your 401(k) or IRA into a Roth account? A Roth account does not have required minimum distributions (RMDs) since the IRS already received its cut of your contributions. You can allow the funds to sit and grow for your entire life (and potentially the life of your spouse as well), without having to strategize and plan for required withdrawals in retirement.

In addition to these important benefits lie several critical advantages worth a closer look.

Lowering your future tax bracket on other income. |

|

|

Assuming you’re able to take qualified withdrawals in retirement, what you pull from your Roth account won’t increase your taxable income. For this reason, Roth withdrawals can be powerful tools for minimizing your total tax liability by keeping your tax bracket lower for other income that does get taxed at the ordinary income tax rate (like traditional 401(k), IRA distributions, and a portion of Social Security) |

Taking advantage of low-income years. |

|

|

Your income will fluctuate throughout your lifetime—and it’s not guaranteed to always go up and up and up. You may need to take time off work to care for an aging parent, raise a child, focus on higher education, or otherwise reprioritize your time. You could also be laid off work during an economic downturn, earn lower-than-usual commissions, or quit a steady job to start building a business. In the years when your taxable income is lower, it’s safe to assume your tax bracket will likely be lower as well. If you have the funds to cover the tax liability of a Roth conversion, this could be an effective way to do the conversion while paying less taxes on it—especially if you anticipate your income rising again in the future. Many retirees encounter a natural lull in their income in the years after they stop working, but before claiming Social Security, pensions, and starting to collect those pesky RMD’s. While it can sound appealing to lock in an artificially low tax bill in those years, our job as wealth advisors is to consider your lifetime tax liability, not just optimizing single years. This is where a change in the status quo can set the stage for longer-term planning via Roth conversions. |

Reducing Medicare premiums. |

|

|

You may be required to pay more than the standard base for your Medicare Part B and Part D based on your modified adjusted gross income (MAGI). This additional premium is called the “income-related monthly adjustment amount (IRMAA),” and it means you could be responsible for paying up to 85% of your Medicare monthly premium, as opposed to the standard 25%.7 In 2025, for example, the portion of the standard Part B premium plan participants are responsible for paying is $185 per month. But if your latest tax return shows a MAGI above $106,000 (or $212,000 for married filers), you’ll have to pay more.7 (When dealing in government time, “latest tax return” means your tax filing from 2 years ago. Therefore Medicare would be looking at your 2024 tax return to estimate your 2026 Medicare premium.) Because withdrawals from a Roth account don’t add to your taxable income, they won’t increase your MAGI. Balancing your other taxable income with Roth distributions can help optimize your MAGI each year in retirement to keep those additional Medicare premiums in check. |

The Value of Roth Accounts in Legacy Planning

While you may be considering a Roth conversion for your own potential tax savings, think even more broadly. When done effectively, a Roth conversion can help minimize your lifetime taxes as a family unit—meaning the benefits impact not only you, but your spouse and children (or other beneficiaries) as well.

We’ve established that Roth accounts don’t have RMDs. You have the freedom to continue contributing to your Roth account throughout your lifetime, and you never have to take a dime out of it if you really don’t want to.

Many retirees like the idea of using their Roth account as a way of leaving surplus retirement savings to their heirs. Similar to the rules for the original account owner, withdrawals of the original contributions are tax-free, and earnings may be withdrawn tax-free as well as long as your beneficiaries meet the requirements. Namely, the account needs to be older than five years before tax-free withdrawals can be made.8

It’s important to note here that an inherited Roth IRA will likley be subject to the 10-year rule, meaning the account must be emptied within 10 years of the original owner’s death. However, certain eligible designated beneficiaries (including a spouse or minor child) are not held to this requirement.8

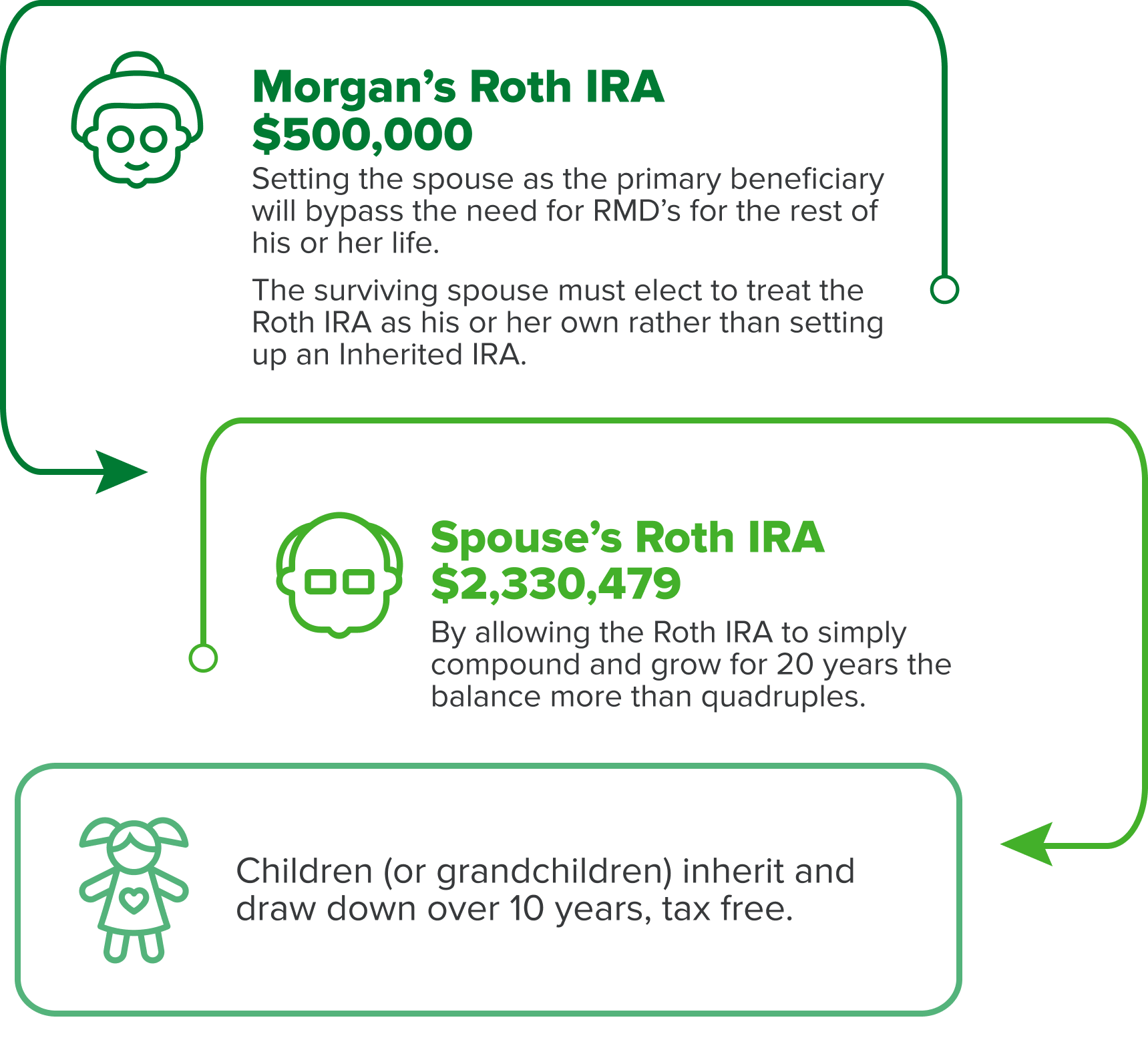

When legacy planning is a priority, it’s critical to work with your wealth advisor and estate planning professional to determine appropriate beneficiaries in order to maximize the tax-free compounding potential of a Roth IRA. Let’s look at an example:

After careful planning and Roth conversions over the years, Morgan has accumulated $500,000 in a Roth IRA at age 70. Let’s assume an 8% rate of return on the Roth investments.

|

If Morgan establishes his or her spouse (who is the same age) as the primary beneficiary of the Roth IRA, the spouse will benefit from a special rule that permits the spouse to skip RMD’s during his or her lifetime as well. After an actuarially impressive 20 years, Morgan’s spouse bequeaths the IRA (which has now reached over $2.3 million) to their children who will have 10 additional years of tax-free growth after considering their annual RMD withdrawals. |

|

Now let’s assume the same facts, except Morgan didn’t consult with a wealth advisor. He or she was so excited to pass wealth to kids and grandkids, all of whom are over 21 years old. Those beneficiaries will have to immediately start taking required minimum distributions, and have lost the power of earning 1.8 million extra tax-free dollars. |

This might feel like an extreme example, but it illustrates the importance of having a knowledgeable advisor to help each step of the way. One might think that the decisions to complete a Roth conversion, of what value, and in which year(s) would be the hardest part. However, these accounts will likely have a life beyond your own to consider, and can have a big impact on the net-of-tax wealth you are able to share.

Why Not Do a Roth Conversion?

Why Not Do a Roth Conversion?

While a Roth conversion can certainly provide some investors and retirees with notable benefits, it’s not for everyone. Before forging ahead, you need to understand the tax benefits of a Roth conversion in relation to your specific circumstances—which may require you to analyze your tax situation today mixed with making some educated guesses about the future.

Let’s break down a few specific instances when a Roth conversion may not be the most ideal option.

Your Tax Rate Is Higher Today Than It Will Be in Retirement

The primary benefit of a Roth conversion is that you’ll be able to enjoy tax-free income in retirement. If you foresee your tax bracket in retirement being the same or lower than it is today, a Roth conversion may not be in your best interest.

But alas, tax brackets behave differently in your working years compared to your retirement years. I’m not opening my trenchcoat to sell you a knock-off tax bracket when you quit working. It’s all about perspective:

- In your working years, you are concerned with managing your marginal tax rate, or the cost of each incremental dollar you earn. In this regard you’re working from the top down, where tax planning means that you’re always concerned with adding to or subtracting from your baseline earnings.

- In retirement, you are concerned with managing your effective tax rate, or the total tax cost as a percentage of your total earnings. At this stage, you are working from the bottom up, carefully crafting the amount and character of your income from the lowest bracket upward.

Let’s look at an example…

The U.S. uses a progressive tax system, meaning your marginal tax rate only applies to your last earnings.

For instance, if you are a W-2 employee earning $165,750, your marginal tax rate (assuming you’re a single filer claiming the standard deduction) is 24% in 2025.9 But that 24% doesn’t apply to the entire taxable income of $150,000—only to the portion that falls within the 24% tax bracket (in this case, that would be $46,650). Other portions of your income will be taxed at the lower tax rates—22%, 12%, and 10%.

Let’s take a look at how your tax bill would be calculated using our progressive tax system:9

| Tax Rate | Income | Total Income Subject to Each Tax Rate | Total Tax Liability Per Tax Bracket |

|---|---|---|---|

| 10% | $0 to $11,925 | $11,925 | $1,192 |

| 12% | $11,926 to $48,475 | $36,550 | $4,386 |

| 22% | $48,476 to $103,350 | $54,875 | $12,072 |

| 24% | $103,351 to $150,000 | $46,650 | $11,196 |

| TOTAL: | $150,000 | $150,000 | $28,846 |

Excluding any additional itemized deductions or credits, your total tax bill on $150,000 would be $28,846 (an effective tax rate of 17.5%). For comparison, a flat 24% tax rate applied to every dollar of taxable income would come to $36,000—a $7,154 difference.

Now, consider your retirement income. Unlike the fairly straightforward tax treatment of a W-2 paycheck, your retirement income will be derived from a number of different sources—all with varying tax treatments.

In other words, the $165,750 W-2 salary you receive this year is entirely subject to ordinary income tax (excluding deductions). But say you plan to live off of $165,750 annually in retirement as well, this time replacing a single-source paycheck with income from Social Security, annuity payouts, bond coupon payments, dividends, and 401(k) withdrawals. Now, even though you’re living on the same amount of income, the tax treatment and total tax liability will be completely different. Because some of your income sources may be tax-advantaged (like Social Security payouts or dividends subject to long-term capital gains rates), your tax liability will likely be less. Not to mention that taxpayers age 65 and wiser may qualify for additional deductions that would further reduce their tax bills.

If that’s the case, you may be better off keeping your retirement savings growing in a tax-deferred 401(k) or traditional IRA. This would mean paying the ordinary income tax as you make withdrawals or take RMDs in retirement, when the composition of your retirement income will likely be more tax varied.

You’re Not Ready to Cover the Tax Bill

Any amount of money you convert from a traditional to Roth account will be subject to ordinary income tax for the year the conversion is completed. While you don’t have to convert your entire pre-tax account into a Roth account, it’s still important to consider how this conversion will impact your tax bill.

You’ll likely need to make estimated tax payments, for example, to stay ahead of the tax liability and avoid penalties come tax time.

If you simply don’t want to cover the additional tax liability right now, or it would put you in a financially uncomfortable situation, this is certainly reason enough to reconsider doing a Roth conversion.

“Can’t I just pay the taxes from IRA withholdings?” you may ask. And we might reply, “can a dog still run fast with 3 legs?” Of course, paying the taxes from your IRA balance is an option, but it means that you’ve diluted the value of what could be going into the Roth account, which can hamper the turbo charging effects of tax-free growth.

You’re Thinking of Donating to Charity

If you’d like to give back generously in retirement, and you have the means to do so, your traditional 401(k) or IRA can be ideal, tax-efficient tools for doing just that—meaning you may not want to get rid of them just yet.

Remember, 401(k)s and IRAs are subject to RMDs. But, you do have the option to donate a portion of the RMDs from your IRAs directly from your account to a qualified charity of your choice. These are called Qualified Charitable Distributions (QCDs), and they offer retirees several advantages.

First, they can be used to satisfy the IRS’s RMD requirement. Because they’re donated directly to charity from your IRA, QCDs don’t increase your taxable income in retirement. And finally, because you aren’t withdrawing (or converting) the funds and taking out taxes, you’re maximizing the impact of your donation.

At first blush, a QCD can be a doppelgänger for taking an IRA distribution and writing a check to the same charity. But, when you factor in various income and deduction limits, QCD’s are reliably more tax efficient than “regular” donations to charity. Think of it as taking one left instead of three rights. The charity will end up in the same place, but the tax route was a bit more efficient for you.

You Have No Heirs

Roth accounts are ideal wealth transfer tools, since they aren’t subject to RMDs and can be transferred to spouses, children or grandchildren in a tax-efficient manner. But if you don’t have any heirs, you may be less concerned about building tax-focused wealth transfer tools. Instead, you may find it easier to enjoy the earlier-in-life tax savings of a traditional account and prefer to just cover the incremental tax liability on withdrawals in retirement.

Is a Roth Conversion Right For Me?

Is a Roth Conversion Right For Me?

The thought of enjoying tax-free withdrawals and no required minimum distributions is appealing, but as we’ve discussed above, Roth conversions aren’t necessarily the best decision for every scenario. As you consider whether a Roth conversion might make sense, when to do it, and how much to convert, take a close look at your tax situation and personal circumstances.

Let’s walk through a few of the most critical key considerations in determining if a Roth conversion really fits into your greater financial goals and retirement needs.

All, Some, or Nothing?

There’s a common misconception that it’s “all or nothing” when it comes to transitioning funds from a tax-deferred 401(k) or IRA into a Roth account. In reality, you can convert as little or as much as you like in any given year. Having that flexibility can make Roth conversions convenient for proactive tax planning.

You might choose, for example, to do multiple Roth conversions over several years in order to generate more tax-free retirement income without increasing your marginal tax rate. This “ladder” approach can help dampen the tax impact of a conversion, so you aren’t taking the full hit in one year.

Here’s what’s important to know about Roth conversions: Each conversion triggers its own five-year clock for penalty-free withdrawals, even if you already have a Roth IRA. This is known as the seasoning rule. If you plan on converting funds from your 401(k) in your 50s and tapping them in your early 60s, you’ll still need to plan proactively to ensure you hit the five-year mark.

One-Time Tax vs. Smaller Payments

Think of a Roth conversion as the tax version of the saying, “short term pain, long-term gain”: You’re choosing to pay a tax bill now in exchange for tax-free growth and withdrawals later. The question is whether that upfront, larger tax bill (even if it’s spread out over years) makes more sense than continuing with the smaller, ongoing tax payments that come with traditional retirement account withdrawals.

There’s no universal breakeven point, since it all depends on factors including:

- Your current tax rate

- Anticipated future tax rates and sources of retirement income

- How long you plan on keeping the funds invested in the account

- Your ability to cover the tax bill

Any amount of pre-tax contributions or untaxed earnings you convert will be added to your ordinary income for the year. That means more taxes now, potentially pushing you into a higher bracket or triggering additional costs elsewhere (such as Medicare premium surcharges or higher capital gains tax exposure).

Keep in mind that covering the tax liability of a Roth conversion can be expensive, and you may want to try paying it from non-retirement funds if possible to preserve the full value of your retirement assets and avoid potential early withdrawal penalties. That being said, if you think covering the tax bill of a Roth conversion using outside resources would strain your cash flow or require selling appreciated assets in a brokerage account (and potentially trigger capital gains), it may be worth holding off—or converting a smaller amount instead.

Your Retirement Income Expectations

If you expect to earn the same or more in retirement—perhaps because of a pension, rental income, or continued part-time work—a Roth conversion could help minimize the impact of higher tax rates later.

Roth conversions often make the most sense during years when your income is temporarily lower. For example, people often experience a “tax lull” during the time between leaving work behind for good and the start of Social Security or RMDs (think late 50s or early to mid 60s). This drop in taxable income can be especially apparent if both spouses retire around the same time. Depending on your financial circumstances, this could be an ideal time to shift pre-tax assets into a Roth account since your tax rate may be unusually low.

Other Factors Impacting Your Retirement Tax Rate

Your tax liability in retirement will depend heavily on your income sources, but there are a few additional variables that can impact your effective tax rate as well. In addition to what we’ve already discussed, here are a few more scenarios to consider:

Medical expenses or high itemized deductions: Generally, you can deduct unreimbursed medical expenses if they exceed 7.5% of your adjusted gross income (AGI).10 If your medical expenses are unusually high and your taxable income relatively low, you could use these deductions to help offset the tax impact of a Roth conversion.

Moving to a state with higher income tax: If you currently live in a state with no income tax but plan to move to one that does tax retirement income, it may make sense to convert now while the state tax rate is effectively 0%. Keep in mind that while your state income tax rate is 0%, you’ll likely still owe federal income tax.

Offsetting losses or deductions: If you have business losses, large charitable contributions, or other deductions that significantly lower your AGI, those could help cushion the tax liability of a conversion.

Market volatility or poor portfolio performance: If your IRA or 401(k) has dropped in value during a market downturn, transitioning the funds to a Roth account at the lower-than-usual value means you’ll owe less tax—and any future recovery will grow tax-free in the Roth.

Capital gains and/or Net Investment Income Tax (NIIT): If your total income (including the amount from a conversion) is high enough, it can trigger additional tax liability. For example, the long-term capital gains tax rate is based on your total taxable income. In 2025, there is zero long-term capital gains tax applied if your taxable income is below $47,025 (or $94,050 for joint filers). If your taxable income is higher, however, you’ll owe either 15% or 20% (or up to 28% under certain circumstances).5

You may also be subject to pay a 3.8% Net Investment Income Tax (NIIT) if your gross income is $200,000 ($250,000 for joint filers) or higher.11 If you’re close to one of these thresholds, it might make sense to hold off on converting (or limit how much you convert).

Understanding Criteria for Qualified Withdrawals

While you can withdraw your contributions from a Roth IRA at any time tax- and penalty-free, that rule doesn’t apply to earnings or funds converted from a traditional account.

To withdraw earnings tax-free from a Roth IRA, you must meet two key requirements. First, the account must be open for at least five years.6

In addition, you must either be:6

- 5 or older,

- Permanently disabled,

- Using up to $10,000 for a first-time home purchase, or

- A beneficiary of a Roth IRA.

If you don’t meet the criteria for qualified withdrawals, you’ll be required to pay ordinary income tax. In addition, you could be hit with a 10% early withdrawal penalty if you take withdrawals before turning 59.5.12

Certain exceptions to the 10% early withdrawal penalty—such as for medical expenses or education costs—come with trade-offs.12 You can’t “double dip” by using the same expense for both a tax deduction and a penalty exception. For instance, if you use conversion funds for qualified education expenses, those expenses won’t count toward education tax credits.

Inheritance Considerations

Though a Roth conversion doesn’t provide immediate tax savings, it can be a powerful tool for legacy planning—particularly for married couples.

As the beneficiary of your Roth IRA, your spouse can treat the inherited account as their own, continuing tax-free growth for years or even decades. This is especially beneficial if you (the surviving spouse) are younger than the original account owner and can benefit from having a longer period of tax-free compound growth.

When one spouse dies, the surviving spouse often faces an uphill financial battle. Generally, the couple’s household expenses only drop by about 20% when one spouse dies, leaving the widow or widower to cover the remaining 80% on their own. At the same time, their tax status adjusts to single filer, and they may see a reduction in pension payments or Social Security spousal benefits. Having a pool of Roth assets (including an inherited Roth account) can help the surviving spouse maintain their lifestyle after losing a loved one without increasing their financial burden with big tax bills.

Medicare Costs (IRMAA)

Some higher-income retirees may be required to pay the income-related monthly adjustment amount (IRMAA), which increases their Medicare Part B and Part D premiums.

For 2025, IRMAA surcharges start when modified adjusted gross income (MAGI) exceeds $106,000 for individuals or $212,000 for couples. And unlike tax brackets, IRMAA tiers are cliff-based—go $1 over the threshold, and you’re in the next tier.13

Roth income can be used strategically to help retirees avoid or minimize IRMAA. Because Roth withdrawals don’t increase your modified adjusted gross income (MAGI), they can be used to manage your taxable income and potentially keep your Medicare premiums lower.

It’s also worth noting that the Medicare premiums you begin paying at age 65 are based on your income from age 63. If you choose to do a Roth conversion in the year you turn 63, for example, this move could increase the first year of your Medicare premiums at age 65—another example of why timing your Roth conversion wisely is so important.

Case Studies

Case Studies

#1: Meet Sarah, 44

Sarah recently left her full-time job to pursue less stressful part-time work before she retires … in about 20 years. She had worked for her previous employer for over 15 years, earning around $250,000 annually by the time she left. Now, she’s earning around $50,000 annually, which handily covers her expenses, as she’s deliberately kept them low and paid off all her debt.

Here’s what Sarah has saved up so far:

- $2 million in her 401(k)

- $1 million in a Roth IRA

- $250,000 in her taxable brokerage account

Sarah is not married and doesn’t have children.

Will a Roth Conversion Benefit Sarah?

Sarah is considering converting her entire $2 million 401(k) into a Roth account by doing small conversions annually for 25 years. In doing so, she would be able to keep her marginal tax rate within the 22% bracket. This conversion would add an additional $21,000 to her tax bill each year for 25 years, which she would plan to pay via tax-loss harvesting from her taxable brokerage account.

By calculating the historical average performance of Sarah’s investments and potential tax liability over time, her financial planner has determined that a Roth conversion will save her an estimated $830,000 in taxes across her lifetime, which they estimate will have her living to age 92. Because Sarah doesn’t have children, she isn’t too concerned about the long-term tax benefits a Roth account offers inheritors. But, because the conversion will save her significantly in taxes across her lifetime, she and her advisor have decided it’s the best option moving forward.

#2: Meet Michael and Sue, 55 and 53

Michael and Sue live on Michael’s $450,000/year salary as an executive at a manufacturing company. In two years, Michael plans on retiring and collecting pension payments, which will amount to around $120,000 a year. Together, they own their family home outright, as well as a rental property with about $200,000 left on the mortgage.

They have two grown children, including a daughter with special needs. As they approach retirement, Michael and Sue are aware of the major expenses coming down the line—purchasing a home for their daughter, traveling often, and renovating their house.

Here’s what Michael and Sue have saved so far:

- $3 million in a 401(k)

- $2.5 million in other retirement plans

Will a Roth Conversion Benefit Michael and Sue?

If Michael and Sue opt for a Roth conversion, spread out across 14 years (around $350,000 per year, with a total value of around $7 million when all is said is done), they can stay within their 24% tax bracket. This conversion will increase their tax bill by about $35,000 each year, but it lowers their lifetime tax liability significantly—by around $900,000. In addition, it will help them build up their tax-free retirement income bucket. By the end of their lives, their Roth account will likely be worth around $13 million—creating a significant tax-free benefit for their children as well.

#3: Meet Diane and Fred, 64

Diane and Fred recently sold their family business for $1.6 million and plan on living on around $100,000 a year in retirement. Because they can live off the sale of their business, they plan on delaying Social Security benefits as long as possible (until age 70). They also don’t have any children, so legacy planning is not a high priority.

In addition to the $1.6 million business sale proceeds, Diane and Fred have $1.75 million in a traditional IRA.

Will a Roth Conversion Benefit Diane and Fred?

First, Diane and Fred will owe taxes on the sale of their business. Off the bat, this will be around $273,000 for the $1.6 million earnings. They plan on living on the earnings from the sale of the business alone until age 70, meaning that for the next six years, they will have little to no tax liability (because they have no meaningful income). At age 70, a percentage of their Social Security benefits will be subject to tax, but since that’s their only form of taxable income, the rate will likely stay within the 12% tax bracket.

At age 73, they will have to start taking RMDs from the traditional IRA, which will boost their taxable income—likely into the 22% bracket.

Diane and Fred could instead choose to do a Roth conversion. In fact, our calculations found that by converting approximately 50% of their traditional IRA to a Roth account, they could save around $369,000 in tax liability across their lifetime. Should they complete the conversion over the course of several years, this would mean their tax liability between ages 65 and 69 jumps from 0% to 24% each year. Once the conversion is complete, their tax liability would fall back down at age 70 to around 12% (accounting for Social Security benefits), before likely jumping back up to 22% by age 83.

Yes, technically, a Roth conversion may save them in lifetime taxes. But does it make sense in this particular case? The problem is, a Roth conversion would significantly reduce their cash flow up front, which may be the time in retirement when they’re looking to be most active and spend more freely. The lifetime savings is also relatively small compared to the $7.8 million or so they’re expected to have accumulated by the end of their life—and with no heirs to worry about, the additional savings may end up causing more stress earlier in retirement than necessary.

This is a scenario in which Diane and Fred would benefit greatly from talking to a financial advisor first.

#4: Meet Christopher, 71

Christopher is a partially-retired university professor. While he no longer works at the university, he still offers some night classes at the nearby community college. This part-time job earns him around $50,000 a year. Christopher’s home is fully paid off, and he has no intentions of moving in retirement. Christopher does have two children, both high earners, and he would like to leave a decent inheritance to them one day.

His part-time income aside, here’s what his other retirement income looks like:

- $7 million in his 403(b) and IRA (both tax-deferred retirement accounts)

- $100,000 in a Roth IRA

Currently, Christopher is comfortably living on about $50,000 a year of taxable income.

Will a Roth Conversion Benefit Christopher?

Christopher will need to start taking RMDs from his tax-deferred accounts in the next two years (when he turns 73). Because he’s accumulated a significant amount of assets in his 401(k) and IRA, his RMDs will likely be substantial. At the same time, his retirement tax buckets are unbalanced. He has just $100,000 in his Roth account (enough to support two years in retirement) versus his $7 million in taxable retirement income.

Before he turns 73, Christopher could convert around $1.091 million from his 403(b) into a Roth account (around $185,000 annually for six years) before RMDs kick in (which will significantly increase his tax rate). Doing so would push his taxable income higher now, but our findings suggest that Christopher (and eventually, his children) would save on lifelong tax liability with a Roth conversion. Not only will his children be able to benefit from a tax-efficient inheritance, but Christopher will save around $147,300 in taxes by converting early in retirement.

How Do I Do a Roth Conversion?

How Do I Do a Roth Conversion?

Once you’ve decided a Roth conversion might align well with your financial goals and tax situation, the next step is to actually move ahead with executing a conversion. The process is relatively straightforward, but it does require you to pay close attention to the details.

Here’s a general look at how to complete a Roth conversion, step by step.

Step #1:

Decide How Much to Convert

Figure out how much of your pre-tax retirement savings you want to convert to Roth. Remember, you don’t have to convert the entire balance of your traditional IRA or 401(k). It’s not uncommon for investors to convert a portion of their account over multiple years instead to minimize some of the tax impact.

As you think about how much money to convert, consider:

- Your current tax bracket and how much “headroom” you have before hitting the next one

- Your ability to pay the resulting tax bill with non-retirement funds

- The potential impact this conversion will have on things like Medicare premiums, capital gains taxes, or income-based programs

You should also consider consulting your tax professional or financial advisor before making major changes to your retirement income strategy. They can help you determine the right amount to convert without unintentionally triggering higher taxes or penalties elsewhere.

Step #2:

Understand What Your Financial Institution Requires

Not all custodians follow the exact same process for Roth conversions. If your traditional and Roth accounts are at the same institution, you may be able to complete the conversion online in just a few clicks. But if you're moving funds between two different institutions, you may need to fill out additional paperwork or request a trustee-to-trustee transfer.

Before initiating the conversion, check with your financial institution to confirm what steps you’ll need to complete in order to open the Roth account, how long the process will likely take, and if there are any fees or transfer restrictions to consider ahead of time.

Give yourself and the financial institution plenty of time to complete the Roth conversion process, so you’re not sweating about getting everything completed before the tax year ends (when the holidays are in full swing, both you and your advisor will want time to focus elsewhere!).

Step #3:

Submit the Required Paperwork

Once you’ve decided how much to convert and confirmed your institution’s process, it’s time to initiate the transfer. Depending on the provider, this could be done online—though some places still require hard copies of the forms sent through the mail. In either case, be sure to keep a copy of the paperwork or confirmation emails for your records.

Step #4:

Monitor the Transfer

After you submit your conversion request, monitor both your traditional IRA and Roth IRA accounts to make sure the transaction goes through as expected. This can take anywhere from a few days to a few weeks, depending on the institutions involved.

If you don’t see the transfer reflected in your account statements within a reasonable amount of time, contact your provider to follow up.

Step #5:

Invest the Funds in the Roth IRA

It’s easy to overlook this step, but once your funds arrive in the Roth IRA, they generally won’t be invested automatically—especially if the conversion involved transferring cash.

Select investments for your Roth IRA based on your goals, time horizon, and risk tolerance. Because Roth IRAs aren’t subject to required minimum distributions (RMDs), they can be better positioned to capture long-term growth. Some investors opt to use their Roth account to invest more aggressively than they do in other retirement accounts.

If you plan to use your Roth IRA as a legacy planning tool or don’t expect to withdraw from it for many years, for example, this could be an opportunity to take a little more risk in return for greater earning potential. But before making any adjustments to your portfolio’s risk profile, talk to a financial advisor about your specific circumstances and goals.

Step #6:

Report the Conversion at Tax Time

Any amount you convert to a Roth IRA must be reported on your federal income tax return. Your original custodian should send you a Form 1099-R showing the distribution from your traditional account, and you will need to file IRS Form 8606 to report the conversion, particularly if you accumulated after-tax savings in your retirement plans.

Form 8606 will be particularly relevant if you’ve made any non-deductible (post-tax) contributions to your traditional IRA in the past. The form helps the IRS calculate how much of your conversion is taxable under the pro-rata rule.

Step #7:

Make Estimated Tax Payments (If Required)

The IRS would like you to make estimated tax payments if you’re expected to owe at least $1,000 come tax time. While there are some exceptions to the rule, neglecting to do so could result in tax penalties.

To avoid potential penalties, you may want to make estimated tax payments for any tax liability associated with the Roth conversion. Even if you’re unsure what your final tax bill will be, these estimated payments can help satisfy IRS requirements—while also mitigating a large surprise bill come next April.

7 Things to Know

7 Things to Know

In this section, we’ve rounded up the “you should really know this” fast facts about Roth conversions. They very well could be the deciding factor for determining when or if a conversion is the right choice for addressing your retirement income needs.

You don’t get a do-over: |

|

|

Once a Roth conversion is complete, you cannot reverse it. In fact, the only other account you’re allowed to roll a Roth IRA into is another Roth IRA. You cannot transfer the funds back into a tax-deferred account, like a traditional IRA or 401(k). |

You could have a big tax bill: |

|

|

The amount of money you convert from a traditional retirement account into a Roth IRA is subject to ordinary income tax the year you convert. If you convert $50,000 in 2025, that will increase your taxable income by $50,000 when you file your tax return come next April. You’ll likely want to keep the funds intact in order to maximize your future retirement income (and potentially avoid a 10% early withdrawal penalty), which means you’ll need to use other means to cover the tax bill (like cash reserves). You may be able to liquidate some of your taxable brokerage account, though this could disrupt your portfolio’s growth path and incur more tax liability along the way. |

Conversions are commonly spread out over several years |

|

|

The purpose of a Roth conversion is to help reduce your lifetime tax liability. To do this, you need to be strategic about when and how much you convert each year. Most people tend to spread out their Roth conversion across several years (even decades) in order to keep their taxable income at a reasonable tax rate. For example, a one-time $1 million conversion will jump you up to the highest tax bracket (37%) and create a significant tax liability—one you may not be able to cover out of pocket. By breaking it down into more manageable, bite-size conversions annually, you can keep your tax rate the same (or only slightly elevated) while still ensuring the future benefits of tax-free retirement income. |

Your rollover could come as cash or investments: |

|

|

If you’re converting a traditional IRA, most of the investments that already exist in the account can be converted directly to a Roth IRA without interference. But if you’re converting a 401(k) into a Roth IRA, you’ll typically receive a check for the cashout value of your account. You’ll need to deposit the check into the Roth IRA and then select investments you wish to purchase. |

Your traditional 401(k) or IRA value is based on market price: |

|

|

You’ll receive the closing market price on the day your conversion is processed. This is what your tax bill will be based on, and how much you’ll receive either as a payout check or IRA rollover. |

You can’t skip your RMDs: |

|

|

If you choose to do a Roth conversion after your RMDs have already started, you must take any required distributions from your IRA or 401(k) for the year before converting the account. Remember, RMDs are also subject to ordinary income tax and will need to be considered alongside the rest of the Roth conversion tax liability. |

Going “all in” on Roth can be a devil’s bargain: |

|

|

If you’re thinking about riding the Roth conversion highway to a lifetime of tax-free income, you may be cutting off your nose to spite your face. Because of the progressive tax system in the United States, age-based benefits for the older and wiser population, and potential state level tax benefits, it can be very attractive to have some un-converted pre-tax savings to draw down at bargain rates in your elder years. |

How Can I Keep Adding to the Roth?

How Can I Keep Adding to the Roth?

Once you’ve successfully converted your traditional retirement account into a Roth account, you’ll likely want to keep adding to it and building your future tax-free retirement income. Here are a few ways to continue growing your Roth account each year.

Contribute Up to the Annual Limit

Roth IRAs have the same contribution limits as traditional IRAs: $7,000, plus a $1,000 catch-up contribution for those who are 50 and better. Keep in mind that converting your traditional account to a Roth IRA doesn’t impact your contribution limits. You can convert as much as you want (keeping the tax bill in mind) from a tax-deferred retirement account, and still make up to the annual $7,000 or $8,000 contribution limit (if you meet the income eligibility requirements).

Rollovers

Once your Roth account is established, you can continue rolling over funds from other retirement accounts including:14

- 401(k) or Roth 401(k)

- Traditional IRA

- SIMPLE or SEP IRA

- 457(b) or Roth 457(b)

- 403(b) or Roth 403(b)

Keep in mind that certain account rollovers are subject to various requirements. For example, you must wait two years after a SIMPLE IRA is created before rolling the funds into a Roth IRA.

Backdoor Contributions

As we’ve shared, Roth accounts are subject to income restrictions. If your annual income exceeds the IRS phase-out limit, you will be ineligible to make direct contributions to your Roth account. However, there are some workarounds to help high earners take advantage of tax-free retirement income.

Called a backdoor contribution, you may be able to make after-tax contributions to your traditional IRA before immediately conducting a Roth conversion (before the contributions have time to accrue any significant value in the account). If any earnings accrue in the account before the conversion, you will need to pay tax on them in the year the conversion is done. But because the backdoor Roth contribution is funded with after-tax dollars, there is no other tax liability.

Mega Backdoor Roth

Some high earners may find the annual contribution limits of a Backdoor Roth conversion too limiting, especially if they’ve already maxed out other retirement plan contributions. In certain circumstances, and if your workplace plan allows it, you may be able to do a mega backdoor Roth conversion.

It’s a little complex, but here’s a simple breakdown:

Max out your pre-tax 401(k) contributions: Contribute to the annual limit of your pre-tax contributions to your workplace plan. In 2025, the limit is $23,500 for those under 50, $31,000 if you’re in your 50s, and $34,750 if you’re between 60 and 63.

Make after-tax 401(k) contributions: You and your employer are allowed to contribute a total of $70,000 ($77,500 if you’re in your 50s or $81,250 if you’re between 60 and 63) to your workplace plan.15 That means you can contribute up to an additional $46,500 in after-tax contributions, assuming you’re under 50 and your employer offers no matching (if they do, you’ll need to subtract that as well). Remember, these after-tax contributions will not be deducted from your taxable income.

Convert to Roth: Some workplace plans allow for in-plan Roth conversions, which enable employees to immediately roll after-tax contributions into a Roth 401(k) plan. If that option isn’t available, you may be able to convert the funds into a Roth IRA. Again, doing so quickly will enable you to minimize taxable earnings within the account.

In order for you to successfully complete a mega backdoor Roth, your workplace plan must allow you to make after-tax contributions (not every plan does). In addition, they either need to support in-plan Roth conversions or in-service withdrawals, which are what you’d need to take in order to immediately convert the after-tax dollars into a Roth IRA.

A mega backdoor Roth is complex, and it’s not for everyone. Check with your advisor to ensure you’ve exhausted other options before pursuing this strategy.

Is a Roth Conversion Right For You?

Is a Roth Conversion Right For You?

Nobody wants to give more away to Uncle Sam than they have to, and preserving wealth becomes increasingly important once you enter retirement. No matter what way you slice it, you’ll have to pay some tax on your retirement accounts. The question to consider at this juncture is whether it makes more sense to pay now, at a potentially higher rate, and enjoy tax-free withdrawals (and potentially tax-free earnings) later on. Or, will it make more sense in the long run to put off the bill until your later years, when your other income sources may be more tax-advantaged?

While you can’t predict everything about your retirement, you can consider your resources and circumstances today. If you haven’t already, speak with a financial advisor or tax professional about your options. Walk through your options using your current tax situation and resources, and see what might make the most sense for you now and well into the future.

Join our email list for updates

Stay in touch by signing up for our weekly newsletter. You’ll be the first to hear the latest updates about Fool Wealth’s transition to Apollon, plus fresh insights on investing and financial planning.